The Industry presents a problematic but memorable premiere: Anne LeBaron’s “Crescent City: A Hyperopera”

The Industry presents the world premiere of Crescent City, A Hyperopera

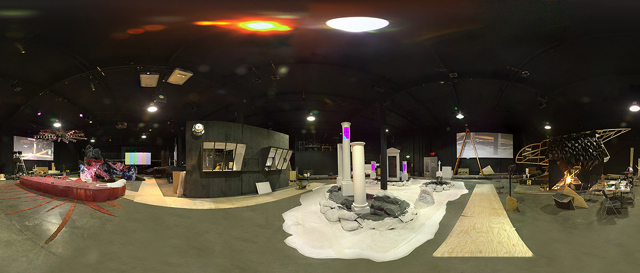

Set Within Cityscape Installations by Six LA-Based Contemporary Artists

The run of this presentation was was completed Sunday, May 27, 2012 at Atwater Crossing in Los Angeles.

Review by David Gregson, Monday, May 28

This was a very special and totally unforgettable event, but was it the salvation of opera in Los Angeles — more wonderful than anything done at the Los Angeles Opera or with the Los Angeles Philharmonic in Disney Hall? Was it more adventurous than things that have been going on for years with the Long Beach Opera?

According to the city’s leading music critic at the Los Angeles Times, with The Industry’s production of Anne Le Barron’s Crescent City: A Hyperopera, “We now have something that can genuinely be called L.A. opera.” In another article by the same writer, the headline crows, “Industry’s remarkable Crescent City reshapes L.A. opera.”

These are truly hyperbolic comments for the so-called “hyper opera,” which, in truth, is a rather conventional opera presented in an unconventional manner. The opera is really very good, mind you — a brilliant modernist pastiche of styles, wonderfully played by a unique orchestral/electronic ensemble and superbly sung by roster of exceptionally fine performers — but the manner of presentation is, in the final analysis, far from satisfactory. Or at it least it seemed so for this viewer and listener. Although I fully realize that standard proscenium stage presentations (depending on where one is seated) are viewed and listened to from different perspectives, normally I am satisfied that I have actually seen something, however skewed the viewpoint, with a reasonable degree of clarity. And normally my ears are not assaulted by voices amplified just short of rock-concert levels of pain.

Allow me to conjure up a hypothetical situation. Imagine that you have been invited to a 12,000-plus square-foot production studio to witness a telecast of a live soap opera episode, but you are told you have to sit still and stay seated in one spot. Settings for the soap opera’s various locales are scattered about this huge space and the performers and TV crew move from one set to another as the story dictates. The soap opera is called Crescent City (a “continuing story” rather like the original series Dark Shadows, full of ghosts, voodoo queens, and assorted supernatural beings and humans in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina in New Orleans) and the settings are a cemetery, a hospital, a swamp, a junk heap, a dive bar and a wooden shack. As the actors and crew move from set to set, you cannot see or hear what is going on well (or at all) because you are stuck in one place. Fortunately, a high definition color television monitor is nearby; what you cannot see or hear in the studio itself, you can see and hear on the TV monitor. At a certain point you might think to yourself, although it was a privilege to be invited here and to see how these shows are really done, I would have been better off at home watching it on my own TV. I just cannot see everything that is going on.

The Industry’s actual production of Crescent City has some of these same problems and provokes similar thoughts. But the many, many artists involved in this giant project felt the difficulties might be solved by (1) allowing a certain number of spectators to wander around the periphery of the studio on a raised walkway; (2) seating some people on beanbags directly in the center of the studio; (3) seating others in a sort of skybox looking down on the action; and (4) putting everyone else in uncomfortable metal chairs around the periphery and make them believe this was all a wonderful idea. Playfully costumed reveling nymphs and dryads would be equipped with little portable TV cameras and could dash about capturing images of “unseen” places and these images would appear (with English subtitles) on four giant screens placed on the four walls. All the performers would be wearing body mikes and all would be synchronized with an orchestra partially seated in a mezzanine. (Some instruments would travel around and not be stationary). All the sets, designed by different local installation artists, would be so wonderful to contemplate that the fact the no ideal unobstructed sight lines would be possible anywhere would not be a problem. Besides, obfuscation would be an essential part of the experience. Not seeing everything clearly would be a sort of aesthetic manifesto.

I began my experience seated in what I am told was the same place (and on the same hard chair) where the aforementioned music critic had been seated earlier in the run. After intermission, however, I and my companion were invited by a patron to join her on the bean bags in the middle of the room. Neither of these locales provided a truly superior or physically comfortable viewing position, and the fact that I have a bad back complicated the matter. To be sure, this was an event for the physically fit, especially those who stood for over two hours (with one 20-minute intermission). I was very interested in what these peripatetic spectators were doing — and from what I could see, they found it difficult to move to the best vantage points without clumping up and blocking everybody else’s view. Frankly, I did not see that much moving about. I think the standees were aware of inconveniencing one another.

I am fond of installation art, but I was not especially smitten by any of the sets I saw; however, the quality of the vocal performances was truly astonishing, and except for librettist Douglas Kearney’s oblique, obscure poetry, I thought the opera’s score to be superb. It could easily be staged in a conventional manner — for, the fact of the matter is, nothing really important is ever going on simultaneously in the six installations. The scenes could be just as effectively presented consecutively. And the videos in this production were mostly blurry, far from the HD images we have become used to. The videos could still be used, however, in a conventional staging.

The stunning cast was dominated by the presence of the phenomenal contralto, Gwendolyn Brown, who plays the central role of the resurrected voodoo priestess Marie Laveau. She invokes the Loa, voodoo gods who are to help her save the flooded city. Another hurricane is on the way, so Marie runs into complications dealing with the various spirits: Baron Samedi (the wonderful lyric tenor Jonathan Mack who also plays a cop); Erzulie (the surprisingly versatile and “charismatic” tenor Timor Bekbosunov, who also plays a slightly terrifying drag queen, Deadly Belle, an entertainer in the Dive Bar); and the two Marissas (Maria Elena Altany and J. Young Yang, an effective pair vocally who also play nurses escaping the flood and snorting coke on the roof of the hospital). The Good Man, whose presence in the city supposedly delays its destruction, was the really excellent bass baritone, Cedric Berry (and I am anxious to hear him again in anything). Berry also played the spirit Baron Carrefour, captain of the supernatural crossroads represented literally in the warehouse setting. Spinto soprano Lillina Sengpiehl was the powerfully touching Homesick Woman whose return home somehow precipitates the death of the Good Man at the hands of a mob.

The opera ends on a wistful, somewhat inconclusive note; but the main point is, really, that everything that happens in Crescent City is a damned shame.

Just how director Yuvai Sharon was able to coordinate all the diffuse elements is a mystery to me. Although I did not adore it, the experience was memorably unique and I am very glad I did not miss it. The conductor, Marc Lowenstein, appears to have accomplished a musical miracle while ensconced in his mysterious loft, invisible to me until I moved to the central beanbags.

I imagine many spectators who attended the Friday night performance I saw ended up in jail. The Los Angeles police and Highway Patrol, or whoever coordinates these things, had set up an utterly inescapable DUI checkpoint starting on The Industry’s main exit street to Glendale Boulevard. The police appeared to be stopping every single vehicle and were looking for drunk after-opera revelers. To my conspiratorial way of thinking, this was a deliberate Gestapo tactic targeting The Industry and the Crescent City location. Fortunately, my companion, had not been drinking anything stronger than coffee. I was not driving, thank God, but in any case had not had anything stronger than one glass of wine over three hours before the DUI stop. To me these stops bring out the libertarian part of my nature: I find them un-American. This one, taking more than 25 minutes out of our evening, was damned inconvenient.

Crescent City: A Hyperopera

Music by Anne LeBaron

Libretto by Douglas Kearney

Story by Anne LeBaron & Yuval Sharon

Directed by Yuval Sharon

Conducted by Marc Lowenstein

Produced by Laura Kay Swanson

Curated by Brianna Gorton

Technical Direction by Eric Nolfo

The Cast:

Maria Elena Altany

Jordann Baker

Timur Bekbosunov

Cedric Berry

Gwendolyn Brown

Ashley Faatoalia

Stacia Hitt

Justo Leon

Jonathan Mack

Gabriel Romero

Lillian Sengpiehl

Chelsea Spirito

Max Wandeman

Ji Young Yang

Visual Artists:

Mason Cooley

Brianna Gorton

Katie Grinnan

Alice Könitz

Jeff Kopp

Olga Koumoundouros

Set Designer: Sibyl Wickersheimer

Lighting Design: Elizabeth Harper

Projection Design: Jason H. Thompson

Sound Design: Martin Gemini

Thank you, David,

I may not be there, but you make me feel as if I were!