Tamino and Pamina Go to Toontown

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the Los Angeles Opera

Review by David Gregson, Monday, November 25, 2013

I love being warned that “purists” are not likely to approve of Los Angeles Opera’s current production of The Magic Flute. What does that term mean anyway? Should Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (assuming purists would demand the German title amongst other things) be staged precisely the way it was when Mozart and his librettist, Emanuel Schikaneder, first presented the Singspiel (for it’s not a grand opera, you know) in 1791 at Schikaneder’s theater, the Freihaus-Theater auf der Wieden in Vienna? As far as I can tell from paintings and drawings, that must have been a fantastic affair. Since then perhaps hundreds of directors and designers have mucked about with the piece including David Hockney, Julie Taymor, Maurice Sendak, Marc Chagall, Theo Otto, David McVicar/John F. Macfarlane, David Poutney, and Zandra Rhodes, to name only those who spring immediately to my personal memory. It is most unlikely that the majority of these offerings historically, some with the dialogue in English and the singing in German, was pure in any way. And I should not forget to mention the innumerable children’s versions of the score which are hacked up and rearranged in ways that, to my mind, quite trivialize the original seriocomic concept.

One of my favorite versions of the opera, aside from several more-or-less fabulously sung “pure” ones that exist without production visuals on CDs or LPs, is Ingmar Bergman’s famous film (1975), sung in Swedish and giving the false impression of having been staged in the Drottningholm Palace Theatre. Bergman took considerable liberties with the original material. In any case, my particular love for this opera focuses on the more serious elements in the music — the scenes written for the noble Sarastro and his followers. The great critic and playwright, Bernard Shaw, described Sarastro’s music as coming from the mouth of God. But I have become accustomed to a lifetime of the the Flute’s comic elements swamping the serious, ritualistic ones — and I must remain content. Ideally the low and the high, the common and the aristocratic, the sacred and profane, the anima and the animus, the fire and water, and the serious and the silly should be in perfect balance. That, indeed, seems to be the whole point. The explicit Masonic ritual given to us by Mozart and Schikaneder is about a kind of Jungian individuation. It is about self mastery, the bringing together of all the various facets of the human personality.

The Queen of the Night and Pamina. Sopranos Erika Miklosa and Janai Brugger. Photo by Robert Millard.

That said, the LAO’s current show — from Berlin’s Komische Oper, by the way, and already a proven smash success in Europe — did not upset this purist in the least. It is the fantastic imaginative creation of director Barrie Kosky working in conjunction with a British theater group known as 1927, presumably as a tribute to the time in which silent films were becoming the talkies. What we see is in essence a highly sophisticated and genuinely astounding full-length animated cartoon in which the premise of Who Killed Roger Rabbit is brought to the stage: human characters interact with the toons. How it is all synchronized in real time with the orchestra and singers is an intriguing mystery and it would be fun to know much more about it. The silent film connection, although clearly inconsistent to the careful observer, is doubly apt — for Hollywood is clearly where silent films gave way to sound, and so-called trials of silence are in important aspect of the Singspiel’s elaborately presented Masonic rituals. I say the silent film references were inconsistent because an extended pink elephant sequence generated by the bird-man Pagapego’s inebriation seems to draw on the famous “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence from Walt Disney’s Dumbo; and, during one of Sarastro’s arias, the eyes peering through cracks in the wall have reference to Orson Welles’s The Trial. Both those films are notable masterpieces from the sound era.

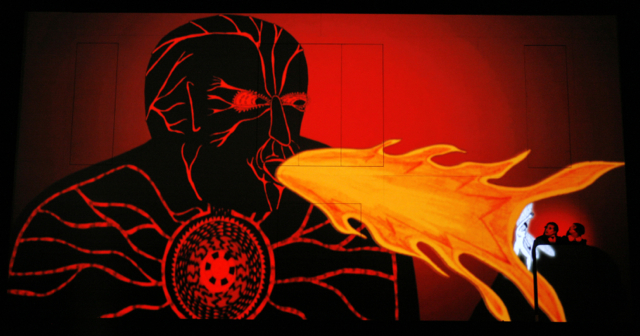

What Kosky and his people have done is eliminate virtually all the Singspiel’s spoken dialogue and replace it with projections in English that mimic the most elaborate title cards from the silent era — the ones that moved or displayed fancy calligraphy. There are many evocations of German Expressionist cinema. The Queen of the Night looks a bit like her nasty servant, Monostatos, and he looks almost like Friedrich Murnau’s vampire, Nosferatu. The ubiquitous stove-pipe hats worn by Sarastro and company make one think of Werner Krauss in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Sarastro’s realm has something of the look of clockwork mechanics (no doubt a symbol of science triumphing over magic), and this seems to reference Jules Verne more than any particular film I can recall, but there is an element of Georges Méliès in it. Tamino looks and acts quite like Buster Keaton in several of his slapstick comedies, and his beloved Pamina looks like Louise Brooks, one of the most memorable stars from Germany’s silent-film era. Brooks, an American, also had a late, brief and mediocre Hollywood career.

Not surprisingly some scenes benefit more that others in this cartoon universe. The famous trial by fire and water (which Prince Tamino and Princess Pamina must endure or die) is almost often always a bust with our hero and heroine wandering around vaguely fiery and watery sets to the accompaniment of a becalmed flute; but here the visuals are stunning and often humorous. One marvelous moment comes when the couple, chained to rocks at the bottom of the sea, rise to the top as their chains dissolve into musical notes.

The magic flute itself, and the accompanying magical chimes, are turned into a white nude female fairy and a chorus of what’s-its — which would be confusing if anyone were following the original story too closely. I have no idea what the supertitles said, for I only glanced at them a few times. In any case, Kosky seems to clarify more than he obfuscates, and that is a good thing. I confess, however, I was not clear how Papageno was a bird man, for he didn’t look like one. He is followed about for the entire opera by the silhouette of a black cat, presumably chasing the bird man or his birds.

This production boasted many musical strengths. I have rarely heard the overture so wonderfully played as it was by the LA Opera orchestra under the direction of James Conlon. The chief difficulty Conlon faced all evening, or so it seems to me, was the stopping and starting over and over for the long silent stretches. These were filled by what might have passed for some clunky upright piano in an old small-town silent movie theater. It was, in actuality, an amplified Hammerklavier, and the music was extracted from Mozart’s Fantasies for Piano, K. 475 in C minor and K. 397 in D minor. But whenever Conlon regained direct control, things were superlative.

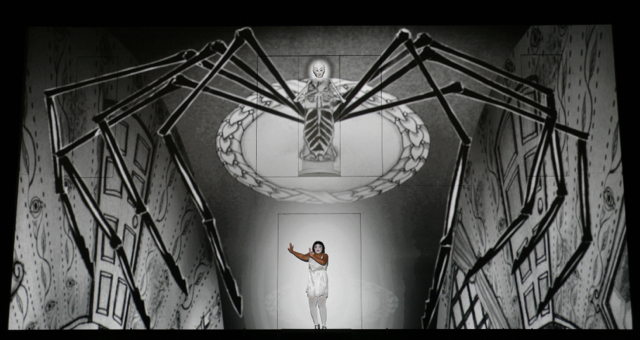

The singing was very much a mixed bag. As Prince Tamino, tenor Lawrence Brownlee was even more marvelous than I had expected from this fine artist. I have never heard him sing Mozart before. Princess Pamina was Janai Brugger, one of those marvelous discoveries who will go far. She is an alumna of the Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist program. The main difficulty baritone Rodion Pogossov experienced as Papageno was being restricted to the postures and positions dictated by the production. These retraints affected everybody. Many artists, presumably fastened securely to their spots, would appear in the projection-bearing back wall via revolving door, perched high and seemingly precariously on tiny ledges. Pogossov had more freedom than that, but I think his vocal performance would have been more effective (more comical and endearing) had he been left to his own devices physically. Unfortunate soprano Erika Miklosa, as the Queen of the Night, seemed to be a mere face sticking through the wall in order to become the head of an enormous spider cartoon that filled the whole stage. With her style so cramped, it’s no wonder she was less than precise in the famous bits of wordless coloratura. Nor could she sink her teeth into the few dramatic passages.

Bass-baritone Evan Boyer had all the notes, but he was not a terribly memorable Sarastro and came nowhere near the sublimity spoken of by Shaw. The three ladies, dressed in their chic ‘30s outfits, were Hae Ji Chang, Cassandra Zoé Velasco, and Peabody Southwell — the latter a favorite of mine from her many Long Beach Opera appearances. The evil Monostatos, no longer a non-PC blackamoor but a fashionable vampire, was tenor Rodell Rosel doing his best in a small role. The Papagena was the most appealing soprano Amanda Woodbury, another worthwhile emerging artist. Doing their duties admirably were the baritone Phillip Addis as the Speaker; Vladimir Dmitruk and Valentin Anikin as the 1st and 2nd Armored Man. The magical boys, sometimes flitting around as butterflies, were Drew Pickett, Charles Connon and Jamal Jaffer. The excellent chorus was led by chorus master Grant Gershon.

I would recommend this The Magic Flute with the reservations I have indicated. I think local audiences are loving it. On the other hand, I do not really hope to see another opera produced in this fashion. I really long for the days when singers and conductor could do their thing and the elaborate spectacle did not become the main reason for the show.

A production of the Komische Oper Berlin.

Presented in co-production with Minnesota Opera.

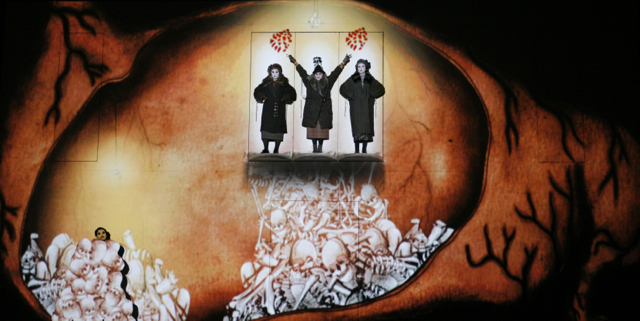

Tamino in the serpent’s stomach. The three ladies admire his beauty as he is digested. Photo by Robert Millard.

CAST

Tamino: Lawrence Brownlee*

Pamina: Janai Brugger++

The Queen of the Night: Erika Miklosa*

Sarastro: Evan Boyer*

Papageno: Rodion Pogossov*

First Lady: Hae Ji Chang+

Second Lady: Cassandra Zoé Velasco+

Third Lady: Peabody Southwell

Monostatos: Rodell Rosel

Papagena: Amanda Woodbury+

The Speaker: Phillip Addis*

1st Armored Man: Vladimir Dmitruk+*

2nd Armored Man: Valentin Anikin+

First Boy: Drew Pickett*

Second Boy: Charles Connon*

Third Boy: Jamal Jaffer

CREATIVE TEAM

Conductor: James Conlon

Director: Suzanne Andrade*

Director: Barrie Kosky*

Animation: Paul Barritt*

Concept 1927 (Suzanne Andrade and Paul Barritt) and Barrie Kosky*

Scenery and Costume Designer Esther Bialas*

* LA Opera debut artist

+ Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program member

++ Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program alumnus

SCHEDULE

Saturday November 23, 2013 07:30 PM

Saturday November 30, 2013 07:30 PM

Thursday December 05, 2013 07:30 PM

Sunday December 08, 2013 02:00 PM

Wednesday December 11, 2013 07:30 PM

Friday December 13, 2013 08:30 PM

Sunday December 15, 2013 02:00 PM

TICKETS and more info.

This production is unique and fantastic and it certainly perks up our jaded appetites, but it sheds no light on the text and inhibits the musical performances by restricting their movements. It fails to move us. It’s certainly something to see, of course; but it does no service to Mozart, unless selling tickets is the object. Aristotle said that “Spectacle is the least important part of drama.” What is deep and moving and true about The Magic Flute is utterly lost in this admittedly enjoyable and dazzling show.

I attended the final performance yesterday and found it musically lacking in drive and sparkling spontaneity for the reasons so well described in your review. I actually got BORED because the performance didn’t have a cohesive, arcing line that ran through the complete performance. However, for today’s public whose minds are splintered by multitasking all day long, it made no difference. Visually arresting production yes, but for sweeping musicality no.

This sounds like a very over the top production with a ton of bells and whistles. This is something that a classical opera usually lacks. Indeed something to look into. Thanks for sharing.