Long Beach Opera revives David Lang’s ‘The Difficulty of Crossing a Field’

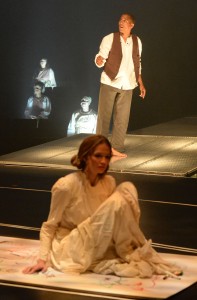

Ensemble, Karole Foreman (Virginia Creeper – Back), Eric B. Anthony (Boy Sam – Front). Photo by Keith Ian Polokoff.

The Difficulty of Crossing a Field

Music by David Lang, libretto by Mac Wellman

Based on a short story by Ambrose Bierce

Review by David Gregson, Tuesday, June 24

When it comes to mysterious disappearances, few celebrated incidents can equal the flight to nowhere that sent CNN into uncontrollable “Breaking News” overdrive earlier this year. Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 was on its way from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing when it lost contact with air traffic control less than an hour after takeoff and then went missing with 12 Malaysian crew members and 227 passengers. What the victims of this presumed disaster must have experienced will very likely never be known, and the families, as well as the public at large, are still wrestling with a mystery that invites every imaginable sort of speculation. Conspiracy theories abound. Even supernatural forces have been contemplated. Motion picture scenarios akin to the TV series Lost have been concocted.

No doubt there is an existential philosopher somewhere with something profound to say about such a disappearance. Or about being and nothingness. To me, disappearance — erasure, if you will — is virtually equal to death.

One of Long Beach Opera’s most impressive productions — perhaps ever — is the David Lang/Mac Welllman The Difficulty of Crossing a Field, first presented at the Terrace Theatre in 2011. Now it returns, just as stunning to see and just as baffling to contemplate as it was the first time around. I personally suspect there is a total void at the center of the enigmatic story which involves the mysterious disappearance of a pre-Civil War plantation owner as reported by a number of witnesses including his wife, a neighbor and a dozen slaves. The opera’s plot is based on a short story (a vignette, really) written by a famous author and San Francisco newspaperman, Ambrose Bierce, who himself mysteriously disappeared in Mexico, never to be found again. This inspires deep thoughts — or rather oblique and ambiguous ones that are expressed in Wellman’s repetitive poetry which endlessly recycles verbal fragments about the significance of undelivered horses, a nation being built or undergoing erasure, questions of personal identity and the so-called mysteries of Selma, Alabama. The music that supports this text is pure David Lang minimalism with much recurrence of thematic material, and the words themselves often shifting into theatrical declamation.

If the production concept were not so fabulously effective, one might accuse stage director/production designer Andreas Mitisek of merely exploiting a gimmick. He puts the audience on the stage, the performers in the vast auditorium, and then appears to ask the question — who are the players and who are the spectators? The audience (seated, may I say, quite uncomfortably close together on chairs upon risers) watches the wrong side of the curtain raised — and then the wonders begin. The cavernous theater auditorium, filled with a thick stage fog that never dissipates, is truly mysterious. The four-person orchestra — the excellent string players of the Lyris Quartet — appear to float magically in a mist off to the right. Five illuminated doors in the distance balcony will become disturbing portals to another world or the entrances to a courthouse. An elevated path seems to float down where the center aisle might be — and Mitisek uses it with all the effectiveness of a Kabuki theater hanamichi ramp. Actors creep around the rows of seats that can barely be discerned through the smoky darkness. Meanwhile, the front stage elevators rise and fall as needed, each time revealing important characters of the drama. It’s really something to see and quite unforgettable.

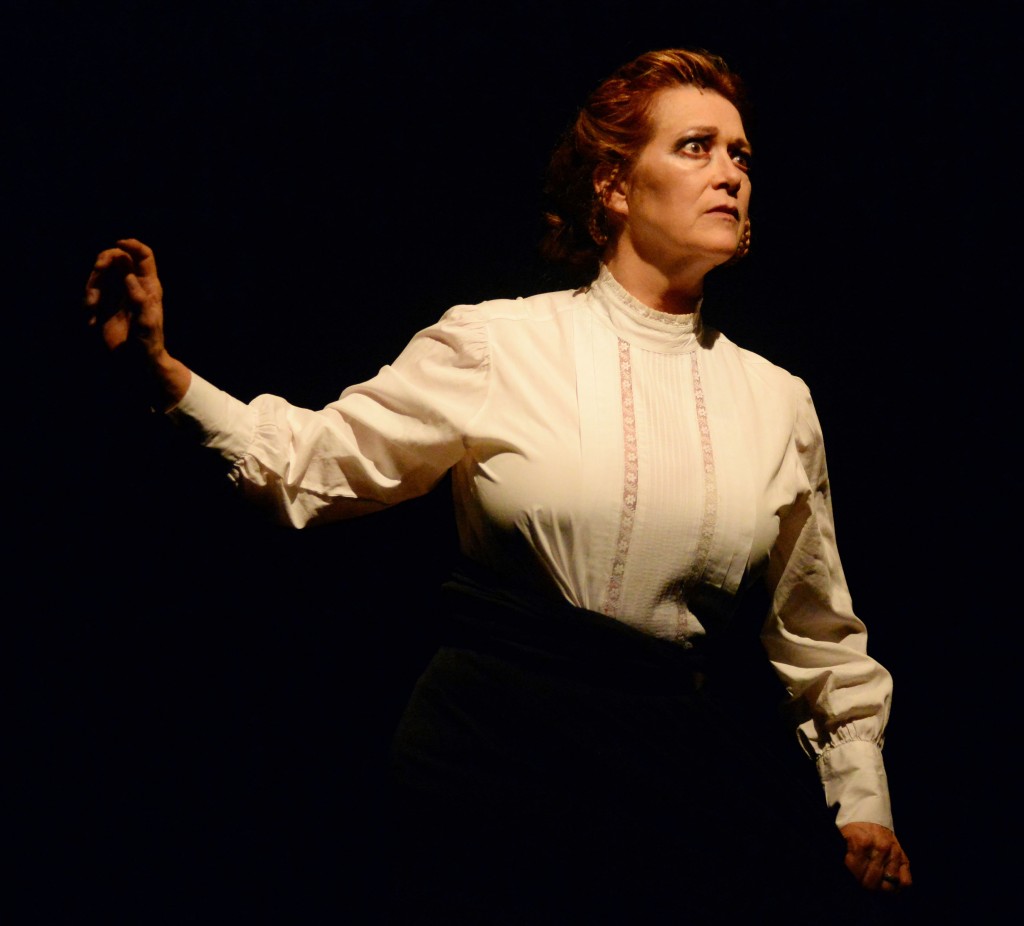

Among the characters who rise and fall upon the (sometimes creaky) stage elevators is the plantation owner’s wife, Mrs. Williamson, played with demented gusto by soprano Suzan Hanson. She is costumed in an enormous black skirt which, if I interpret this garment correctly, is draped about the high roof upon which she is supposed to be sitting as she surveys the world in her increasing madness. It is no easy thing to see your husband go “poof” into non-existence, so she understandably undergoes an existential crisis.

The weirdly charismatic Mark Bringelson plays Mr. Williamson himself, at one early point in the opera chomping on a cigar with an air of detached arrogance as he takes forever to get dressed. It’s hard to imagine better casting. He is also the judge, booming from on high during the inquest. Soprano Valerie Vinzant is superb as “the Williamson girl,” a character not mentioned by Bierce (to my recollection) and seems to be a sort of pre-computer Facebook psychic drawn into mystic contemplation. She’d have a website and Twitter account today. I am curious if “entertainer” Eric. B. Anthony does not imagine his character, Boy Sam, is in fact the illegitimate son of Williamson — not to mention somehow involved with the Williamson girl, but I was unable to stay for what I take to have been a very helpful question-and-answer period offered by the performers immediately following the conclusion of the opera.

Imposing baritone Robin Buck was a powerful presence as the neighbor, Armour Wren. Kristof Van Grysperre conducted effectively from a huge video screen at the back of the seated spectators.

Valerie Vinzant (Williamson Girl – Front), Eric B. Anthony (Boy Sam – Back), Ensemble. Photo by Keith Ian Polokoff.

I thought I would follow these comments with what I wrote back in 2011.

“One of my closest friends, now an American citizen, is a Parsi Indian from Mumbai. I am always intrigued by his reactions to my innumerable operatic excursions. Because he has yet to succumb to the arcane charms of Western opera, he never accompanies me on these adventures — but he seldom fails to make insightful comments on them.

“When I told him about Long Beach Opera’s The Difficulty of Crossing a Field … my friend deftly dismissed the whole concept as somewhat old hat: ‘This idea of a man disappearing and thereby inspiring a narrative concerning the vanishing is an old one. We have it even in India, notably in an interesting film by Mrinal Sen called Ek Din Achanak (‘One Day Suddenly’). A respected retired professor and father of a middle class household tells his family he is going across the road for cigarettes and then never returns. This causes a whole lot of soul searching on the part of his family.’

“The extremely brief Bierce story implies somewhat more than soul-searching, however. The central character (or non-character, as the case may be) is Mr. Williamson, played superbly in this LBO show with a sharp edge of unpleasant scariness by Mark Bringelson. A slave owner in Selma, Alabama, circa 1854, Williamson causes widespread existential confusion and inexplicable anxiety by strolling across a field and suddenly vanishing from view and apparently from this earth. He becomes a non-person.

“The African-American slaves Williamson ‘owns’ are, of course, non-persons in a different sense. They are not allowed to participate in the inquest over the matter — or as Bierce puts it, ‘The servants were, of course, not competent to testify.’ They are invisible, like the protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (one of the great American novels). On the other hand, the white boy, James Wren, seems to have testified only to have his comments stricken from the record. It is he who claimed to have actually seen the vanishing. Thirteen-year olds may be non-persons too.

“So, in this mysterious story and the suggestive quasi-operatic drama made from it, we are allowed to speculate: The Rapture, so much in the news of late if not in 1854, is an impossible explanation — unless Yahweh truly does approve of slave holders as he clearly seems to in the Old Testament. That old sinner Williamson go to Heaven? I don’t think so. Perhaps he walked into one of those dimensional voids described by Dr. Hem of Leipzig (and explained in the LBO program).

“Anything is possible: he could have been murdered for any number of possible reasons and his body disposed of. Does it have something to do with his horse trading with Mr. Wren? Perhaps some weird Selma African voodoo witchcraft wiped him out. Or he could have just gone “poof” from spontaneous combustion. Or he could have simply gone away forever someplace and taken on a new identity.

“Whatever the case, everybody has a different perspective on the matter. And for Mrs. Williamson (wonderfully incarnated by the versatile and ever-fabulous soprano/actress Suzan Hanson), it is an existential crisis of the first magnitude — at least the way Lang and Wellman would have it. She goes mad and sits on top of the roof of the house contemplating the mysteries of being and nothingness. Or at the very least, of no longer being Mrs. Williamson.

“Bierce reports this in what to my way of thinking is a brief newspaper article. Bierce was a newspaper man, after all. It’s difficult to see this extremely short story as having the depth and complexity of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon in which the story of a rape and murder is told by an accidental witness; the alleged rapist/murderer himself; the woman who was raped; and the ghost of her murdered husband. Nevertheless, we learn from Lang and company that Bierce wrote a story on which Kurosawa based his famous film, and Difficulty adopts some of the same trial format. This Kurosawa/Bierce connection, previously unknown to me (a great fan of the film) is most interesting, although I wonder if there isn’t less to all of this than meets the eye.

“Quickly we are thrown into the philosophical realm of being and non-being. That’s the great existential conundrum. People and things exist and then they don’t. Death, non-being, is an absurdity. Jean-Paul Sartre has a thing or two to say about all this, and Ambrose Bierce too, but not very much. Yet Lang and Wellman run off on the subject in a rather pretentious way that raises more questions than it answers — which, in fact, seems to be the entire point. The text is at times exasperating and even tedious at a mere one hour and 15 minutes. The music, however, is highly appealing and effective (played with authority by the Lyris String Quartet), but the text loops around on itself, often evoking Gertrude Stein’s elliptical verse. But not in such a good way: Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts and The Mother of Us All seem to me to be genuine masterpieces — with more than a little help from composer Virgil Thomson.

“My Indian friend also told me vis-à-vis the plot, ‘I think gimmicks are the last resort of the clever artist, never the great one.’

“For a moment I thought he had in mind my emailed capsule description of the production: “A striking aspect of all this was that the entire audience was seated (uncomfortably) on stage facing out into the rather vast auditorium of the Terrace Theatre. When the curtain went up, the auditorium was revealed to us as a gaping black chasm with fog everywhere obscuring our vision. A small orchestra literally seemed to float in space somewhere in the distance. Actors emerged from all sorts of unexpected places among the rows of seats and then vanished into a void. Much use was made of the two-section pit elevator. The visuals were stunning and even incorporated the distant doors of the balcony. A metal hanamichi runway slashed down the center of the orchestra stalls and was used effectively in the perplexing disappearance.

“I forgot to say that looking out at a non-existent audience was a perfect metaphor for the entire work. Sometimes gimmicks transcend mere gimmickry! Take for a random example Haydn’s “Farewell Symphony” which I heard and saw at the San Diego Mainly Mozart Festival only a few days ago. A great piece despite the musicians who vanish gradually from the stage until only two instruments are playing — and you can’t see them because the lights have been turned off.

“I thought this difficult field was one of the finest and most inspired achievements of LBO’s artistic and general director/stage director/production designer/total genius Andreas Mitisek. Lighting designer Dan Weingarten’s work was also utterly dazzling. The ensemble of black performers could not have been improved upon. The conductor, not Andreas for a change, was Benjamin Makino, also serving capably as chorus master.

“My companion/colleague Brenda and I were in love with Eric B. Anthony who played Boy Sam. A charmer with a lovely voice. Valerie Vinzant was superb as the Williamson Girl (even when literally uttering crap), and Robin T. Buck made a very strong impression as Amour Wren and Andrew.”

Below are listed the current performers to whom praise is due.

Meanwhile, a reader has commented on some of the post-performance comments of the participants. “Sorry you missed the question period. It was fascinating. The singers had very different takes on their parts and what happened to Mr. Williamson. The erasure of slavery? The erasure of a person? The erasure of the old to make way for the new? Sam, the house servant, might be the half-sister of the Williamson Girl. The horses might be the slaves themselves — treated like animals. Was Mr. Williamson killed by the slaves? His brother? Did he fall into a sink hole? Was he abducted by some greater force? Did he skip town to avoid a problem? One performer said every line of the original story is in the libretto and commented on the repetition.”

Mark Bringelson (Magistrate – Top), Robin Buck (Andrew – Bottom), Ensemble. Photo by Keith Ian Polokoff.

PERFORMANCES

Sun. June 22, 2014 @ 7pm

Sat. June 28, 2014 @ 8pm

Sun. June 29, 2014 @ 2pm SOLD OUT

Terrace Theater

300 E. Ocean Blvd., Long Beach

Run time: 80 minutes, no intermission

Sung in English with English Supertitles

Cast:

Mrs. Williamson: Suzan Hanson

Mr. Williamson: Mark Bringelson

Williamson Girl: Valerie Vinzant

Boy Sam: Eric B Anthony

Armour Wren/Andrew: Robin Buck

Woman/Ensemble: Lindsay Patterson

Man/Ensemble: Michael Paul Smith

Ensemble: Saundra Hall Hill, Jennifer Lindsay, Matthew Lofton, Marcus Page, Alex Perkins

Conductor/Chorus Master: Kristof Van Grysperre

Stage Director/Production Designer: Andreas Mitisek

Light Designer: Dan Weingarten

LYRIS QUARTET:

Alyssa Park, violin; Shalini Vijayan, violin;

Caroline Buckman, viola; Timothy Loo, cello