My 1997 Review of “Hopper’s Wife” at Long Beach Opera

By David Gregson

Not intended to be amusing, but nonetheless failing to disarm my sense of

what’s funny, are the little signs taped up around the Knoebel Dance Theater

warning the audience about the hazards of the Long Beach Opera’s world

premiere staging of “Hopper’s Wife”.

In trying to remember exactly what was printed on those signs, I find my

imagination has run away with me slightly.

WARNING: “HOPPER’S WIFE” MAY BE HAZARDOUS TO YOUR MENTAL AND PHYSICAL HEALTH !!!

THE OPERA CONTAINS:

FULL FRONTAL NUDITY

OFFENSIVE LANGUAGE

AN OUT-OF-FOCUS PORNOGRAPHIC FILM CLIP

POSSIBLY CARCINOGENIC STAGE FOG

VERIFIABLY CARCINOGENIC SECOND-HAND CIGAR SMOKE

EAR-SPLITTING GUN SHOTS

A PERPLEXING PRE-MILLENNIAL POST MODERN LITERARY TEXT

A CHALLENGING MUSICAL SCORE

OUTRAGEOUS DISTORTIONS OF THE REAL LIFE OF EDWARD HOPPER

RECYCLED SCANDALOUS HOLLYWOOD GOSSIP

The opera, directed by Christopher Alden, was composed by Stewart Wallace

to a libretto by Michael Korie. This is the same trio that brought Harvey

Milk to the San Francisco Opera last season. Alden (quoted in the Los

Angeles Times) said that he felt Harvey Milk was Up With People

compared to this one!

The cast and personnel:

Mrs. Hopper: Juliana Gondek (mezzo-soprano)

Hopper: Chris Pedro Traka (baritone)

Ava: Lucy Schaufer (soprano)

Conductor: Michael Barrett

Director: Christopher Alden

Set and costume design: Allen Moyer

Lighting design: Heather Carson

The piece is scored for a chamber orchestra consisting of violin, cello,

flute and piccolo, B-flat and E-flat and bass clarinets, bassoon and

contrabassoon, saxophones (soprano, alto., tenor, baritone), trumpet and

piccolo trumpet, horn, tuba and percussion. This ensemble is seated on

stage, halfway off stage right. The set, a tipsy monochrome rendering of

Hopper’s “The House on Pamet River”, fills the stage floor and most of the

back, stage left.

The story generates itself from a post modern play on words: Hopper’s wife

becomes Hedda Hopper. It’s a joke, see. My only doubt is to whether a joke

like this one can generate anything of lasting value.

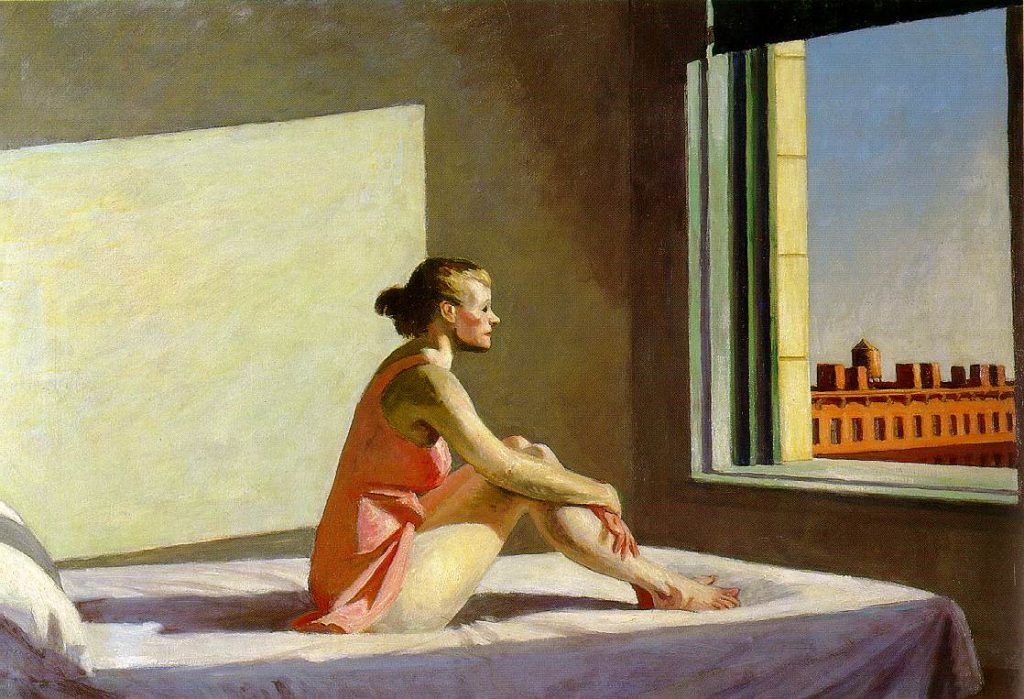

The first part of the opera finds its “inspiration” in a series of Hopper

paintings, many of which are faithfully reproduced in a handsome

desk-top-printed libretto. At the beginning of the piece, Hopper is

painting Ava (in a setting and pose recalling Hopper’s “Soir Bleu”), plying

her with flattering descriptions of a metaphoric vine of roses growing

inside her. Ava repeatedly opens or removes her blue, sheer, sleeveless

peignoir to reveal herself in the nude. Mrs. Hopper comes home from a movie

and hat-buying spree to find her services as a model supplanted by Ava’s.

The opera then commences a series of mini-character studies and

reminiscences based on Hopper paintings in which a model is shown wearing a

cloche hat (“Automat”), a straw summer sun hat (“Summertime”), a bathing cap

“Seawatchers”), and a stripper’s red wig (“Girlie Show”).

The hats, of course, gradually become the hats of Hedda Hopper. When Mrs.

Hopper has finally left her abusive husband for Hollywood, she takes Ava

with her. Ava (soon to be Ava Gardner) is already a veteran of Hollywood

and its sleazy ways. In a long scene that requires the soprano to bathe

naked in a tub whilst being painted by Hopper, we learn many details of her

— ahem! — services to Hollywood agents, none of which services are

printable in most media outlets!

In fact, I imagine would be thrown off Opera-L were I to repeat the lyrics of

Hopper’s “aria” about a visit to a pornographic movie. Let’s just say, the

acts committed and the various fluids and other substances generated by

these acts produce a lovely vision of color and texture that Hopper praises

as true art.

I have two, I suppose absurd objections to this scene. I cannot see what

the scene does to shed light on the work of Hopper. The praise of color and

texture sounds more like something that might come out of the mouth of

Jackson Pollock. And I have my doubts about the accessibility of color

pornographic peep shows given the time reference of the opera. However,

since the opera is obviously a post modern playing around with ideas, none

of which can be taken very seriously, I retreat to my own admission that the

objections are absurd.

Somewhere in all this we are meant to feel the Hopper character struggling

between his impulses toward high art and the low: the Apollonian and the

Dionysian, as it were. I think a rough version of this dichotomy is helpful

here, since the entire opera seems to deal with cultural extremes. Hopper,

the great Apollonian priest of visual objectivity, succumbs to pornography

and ultimately drowns himself. Hopper’s wife. escaping from a stifling

relationship and the art she doesn’t fully understand (she actually burns

her husband’s paintings after his death), ends up in Hollywood as the high

priestess of smutty gossip and tastelessness. The opera closes with Mrs.

Hopper posing as the Columbia Studios logo. The gunshots (remember the

gunshots?) occur as Mrs. Hopper shoots Ava presumably to death — a touch

added by Alden, I’d guess, since I don’t see it in the libretto.

The singers are fabulous. My hat’s off to a soprano who can sing and act

with her clothes off. This is no brief glimpse of nudity, mind you.

Schaufer (Ava) has a gorgeous voice, excellent diction, and (fortunately) a

voluptuous figure. This is no role for Jane Eaglen, I can assure you (and

I’m certain she wouldn’t want to sing it anyway). Gondek (Mrs. Hopper) is

also vocally gifted, and a great comic actress: but I had some trouble

making out her words at times. Trakas (Hopper) has an extremely attractive

baritone. He’s appeared as the Count in Figaro at Spoletto and Dandini at

the Washington Opera. I would imagine he was excellent. (Anybody hear him in

those roles?

The music is such a pastiche, I find it very hard to evaluate. Like some

other contemporary “art” composers who try on jazz idioms, Wallace achieves

only an awkward lumpiness in his attempts at blues. Overall, the score lacks

rhythmic interest, at least in the sense that Adams. Glass, Reich etc. have

rhythm. There is no propulsive drive. The declamatory/lyrical vocal lines

emerge over a wash of atonal smears. This, of course, is only a first

impression. In a work of this complexity, it is difficult to say what my

ultimate judgment of this music would be — but it did not appeal to me

emotionally, nor could I make coherent sense out of it on first hearing.

The musical idiom is not unfamiliar to me, but I was initially unbeguiled.

Barrett conducted with authority and conviction.

This was a co-production of the LBO and the 92nd Street Y. Interested New

Yorkers can post on this sometime in the future. It’s an entertaining piece

— and I laud the LBO for having the courage to put it on. This, with the

“double bill” of Janacek’s “From the House of the Dead” (which I reviewed

yesterday) made for an unusually stimulating afternoon of musical theater.

Knoebel Dance Theater is on the campus of California State University, Long

Beach, where the LBO is now in residence.