Verdi’s ‘Falstaff’ is a winner for San Diego Opera

Soprano Maureen McKay is Nannetta and baritone Roberto de Candia is Falstaff in San Diego Opera’s FALSTAFF. February, 2017. Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson.

Review of opening night, February 18

By David Gregson

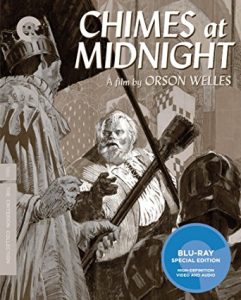

Although I have ample reason these days to cringe at its unrelenting ooze of “fat” jokes, Verdi’s Falstaff remains a personal favorite of mine, high on a list of what I regard as the world’s greatest operas. But this is not so much for the ingeniously crafted libretto of Verdi’s collaborator, Arrigo Boito, as it is for the brilliance of the music itself. For many of us who came, sometimes reluctantly, from the world of pure theater into the world of opera, The Merry Wives of Windsor is one of Shakespeare’s weaker plays, and certainly the weakest when it comes to the treatment of the Fat Knight, Sir John Falstaff. But “Merry Wives” is Verdi’s chief vehicle. In the two parts of Henry IV, Sir John is a most memorable presence — which is why Boito extracted several of the speeches for Falstaff, including the great speech about honor. But really — where is this character without his beloved Prince Hal as a foil? The Verdi opera libretto is a far cry from Orson Welles’ Falstaff (better known as Chimes at Midnight), one of the very best Shakespearean adaptations ever, and now newly available on a Criterion Blu-ray and DVD. The film evolved from Welles’s earlier stage works about the character.

Despite the loss of the substantial history dramas that frame Falstaff at his best, Verdi and Boito mine gold from thin materials. Comically vain and corrupt (yet somehow lovable), Falstaff courts two of Windsor’s merry wives at once, all the time with a eye to their husband’s fortunes. He gets his comeuppance twice: first by being stuffed in a laundry basket which is emptied into the Thames; and next when tormented by the townspeople disguised as witches, fairies and goblins, at midnight near the spooky Herne’s Oak. In this final scene, the poor fat man, tricked into his masquerade as the Black Huntsman, literally wears the horns of a cuckold. During these scenes, Verdi and Boito make wonderful use of two young lovers, Fenton and Nanetta, and they get maximum milage out of several familiar Shakespearean ruffians, Bardolfo (Bardolph), Pistola (Pistol) and Dr. Caius. It’s a neatly woven comic fabric.

So for me personally, and for a very many musicians, Falstaff is almost mind-bogglingly brilliant. Time after time one is in awe of what the composer is doing. His melodic inspiration is virtually unflagging. And the ensembles are enormously clever, and often, I imagine, very difficult to coordinate. I found myself gasping on opening night as the young tenor (Fenton, sung sweetly by Jonathan Johnson) spun out a lovely lyrical line while gaggles of crazy men and women chattered madly on in complicated counterpoint. This is the opera, one recalls, that ends with an elaborate fugue in which the world is characterized as totally mad.

(L-R) Soprano Maureen McKay (Nannetta), mezzo-soprano Kirstin Chavez (Meg Page), soprano Ellie Dehn (Alice Ford), and mezzo-soprano Marianne Cornetti (Mistress Quickly) in San Diego Opera’s FALSTAFF. February, 2017. Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson.

I remember vividly the very first Falstaff I ever heard, with Sir Geraint Evans in the title role, and with Thomas Stewart as Ford, and Giulietta Simionato as Mistress Quickly. It was a San Francisco Opera production which later traveled to San Diego with a slightly different cast. And here’s a program to prove it courtesy of the San Francisco Opera. In those “olden times,” one had to take out a score and an LP to study the opera before one went. There were no supertitles back then, so if you wanted to know what people were singing, you had to be prepared. It was during my very first live exposure to the piece, by the way, that I learned of the reverence for it shared by serious musicians. I saw some of them whom I knew well attending an opera, Falstaff, for the very first time. There was much breathless praise for the work to be heard during the intermissions.

This late Verdi masterpiece, not incidentally, is known as a “conductor’s opera,” and it is represented brilliantly in this regard on recordings. The Leonard Bernstein set (featuring baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and the Vienna Philharmonic) has been famous for its quicksilver charms from the moment of its first release. (I happened to catch Fischer-Dieskau in the role once in Munich). But one can also own Arturo Toscanini’s recording conducted at a breathless pace with Guiseppe Valdengo as Falstaff, a remarkable document in a way, because Toscanini was a champion in the revivals of the work when it had fallen into a period of relative neglect. Several other terrific recordings exist including one that features Sir Georg Solti, with the incomparable Sir Geraint Evans (still the best Falstaff I ever saw live on the stage) and the Berlin Philharmonic. It’s impossible to overlook Herbert von Karajan’s recording, not only for the conducting but because of Tito Gobbi’s priceless vocal characterization.

All of that said, I would not have called Falstaff a “conductor’s opera” on opening night here under the leadership of Daniele Callergari, even though the San Diego Symphony performed admirably. I often wanted to jump up, grab the stick and start leading in the band (if I may make a comic reference to Betty Comden and Adoph Green’s lyrics for Bernstein’s On the Town). I missed a sense of shapeliness and propulsive drive. But, it was all certainly good enough and was buoyed by an exceptionally fine cast of singers.

Baritone Roberto de Candia was a first-rate Sir John Falstaff, prissily narcissitc and preening, and very satisfying vocally. I suspect he would have made an even greater impression had he been left to devices of his own invention and had not been hampered by the stage director. For instance, a classic moment in the role (and I do mean “moment”), is one of the those many astounding brief melodic passages that make up so much of Verdi’s delectable musical fabric in the opera as a whole. It’s the “Quand’ era paggio” passage in which Falstaff recalls his youth as a slender attractive page boy. This moment should belong entirely to the baritone — and oh, what Geraint Evans made of it! Here you can listen to seven famous baritones singing this priceless little ditty. But poor Mr. de Candia was upstaged by unnecessary comic shtick. I think he was dodging things being thrown at him.

Baritone Roberto de Candia is Falstaff in San Diego Opera’s FALSTAFF. February, 2017. Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson.

My impression is that the stage director, Olivier Tambosi, is being much admired for the comic touches he has added to the opera, but I thought his crowd scenes lacked focus or were overly frantic as in the laundry basket scene when the hellzapoppin went so far overboard as to stop making sense. Despite the use of follow spots in the last scene, things were dimly lighted and hard to see. He also had a tendency to stage scenes in a confusing manner. Why would Dame Mistress Quickly be bowing to the audience instead of addressing Sir John when she comes to call on him with her famous refrain of “Reveranza”? I thought there was altogether too much vague character interaction throughout the evening and I found it baffling. There were totally botched bits, as when Ford and Falstaff are trying to pass though a doorway. They defer to one another until they finally decide to go through the doorway together at the same time. In this production there was no doorway and the whole comic scene failed to make its point.

And even though Frank Philip Schlössmann’s sets were generally attractive, a sort of vague evocation of the interior of an Elizabethan playhouse with some pop-up stuff here and there, why put players into a sinkhole in the middle of the stage? They looked as if they were wading in a shallow pool with a open red wooden fan behind it. And then they would climb down and up from it. Maybe people in the balcony could make sense of it. I couldn’t. There was never any real sense of place. I think Schlössmann’s costumes were, in their way, far more successful than the sets. Falstaff’s crimson fancy suit and plumed hat was most impressive.

Baritone Troy Cook is Ford and baritone Roberto de Candia is Falstaff in San Diego Opera’s FALSTAFF. February, 2017. Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson.

Because Verdi’s opera is noted for its carefully woven tapestry of melodic fragments, it’s sometimes forgotten that there are, in fact, extended passages that might be in any of the composer’s more widely loved works. Master Ford’s jealousy scene echoes Otello, and baritone Troy Cook was wonderful in it, even rolling around on the floor at one point. His voice is smaller than de Candia’s, but the two men were well matched in their wonderful scenes together. Soprano Maureen McKay’s Nanetta was perfectly charming in every way, and she sang the long aria of the Queen of the Fairies enchantingly. I also loved her in the gorgeously repeated refrains of “Anzi rennova come fa la luna.” The whole Fenton/Nanetta exchange is engraved on my memory after all these years. Just enchanting!

Soprano Ellie Dehn was one of the better Alice Fords anyone could wish for, and as an ensemble, the women collaborated with both precision and comic flair. Mezzo Marianne Cornetti made a good impression (especially vocally) as Dame Quickly — despite exits and entrances from indefinite locations and all that continual comic bowing. As if the opera libretto did not have enough fat jokes already, she seemed to be on the verge of deliberately toppling over from time to time, another of the stage director’s inspirations no doubt. And the men, listed below, also made for an excellent ensemble. The San Diego Opera chorus excelled throughout. Bruce Stasyna is chorus master.

I think I may be rather alone in my objections to what is wrong in this Falstaff. Everyone seemed to love it. I certainly regard it as a major success for San Diego Opera.

And here’s a story from the New York Times about Carlo Maria Giulini’s Falstaff in LA in 1984. Seems like centuries ago! I have always thought of that performance (with baritone Roberto Bruson) as the beginning of the LA Opera. As I recall, I was not wild about Bruson.

HEAR Sir Geraint Evans sing about “honor”.

CAST

CAST

Roberto de Candia — Sir John Falstaff

Ellie Dehn — Alice Ford

Troy Cook — Ford

Maureen McKay — Nanetta

Jonathan Johnson — Fenton

Marianne Cornetti — Dame Quickly

Kirstin Chávez — Meg Page

Simeon Esper — Bardolfo

Reinhard Hagen — Pistola

Joel Sorensen — Dr. Caius

Daniele Callegari — Conductor

Olivier Tambosi — Director

Frank Philip Schlössmann — Set and Costume Designerin

Christine A. Binder — Lighting Designer

PERFORMANCES

SAT, FEB 18 AT 7PM

TUE, FEB 21 AT 7PM

FRI, FEB 24 AT 7PM

SUN, FEB 26 AT 2PM

San Diego Civic Theatre

1100 Third Ave, San Diego, CA 92101

Soprano Maureen McKay (Nannetta) and tenor Johnathan Johnson (Fenton) in San Diego Opera’s FALSTAFF. February, 2017. Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson.

When I sit and listen to a symphony,

why can’t I just say the music’s grand?

Why must I leap up on the stage hysterically?

They’re playing pizzicato

and everything goes blotto!

I grab the maestro’s stick and start leading in the band!

Carried away!

Carried away!

I get carried away!

Betty Comden and Adolph Green