Regietheater Meets Regietheater in Gedeon/Brook ‘La tragédie de Carmen’ at San Diego Opera

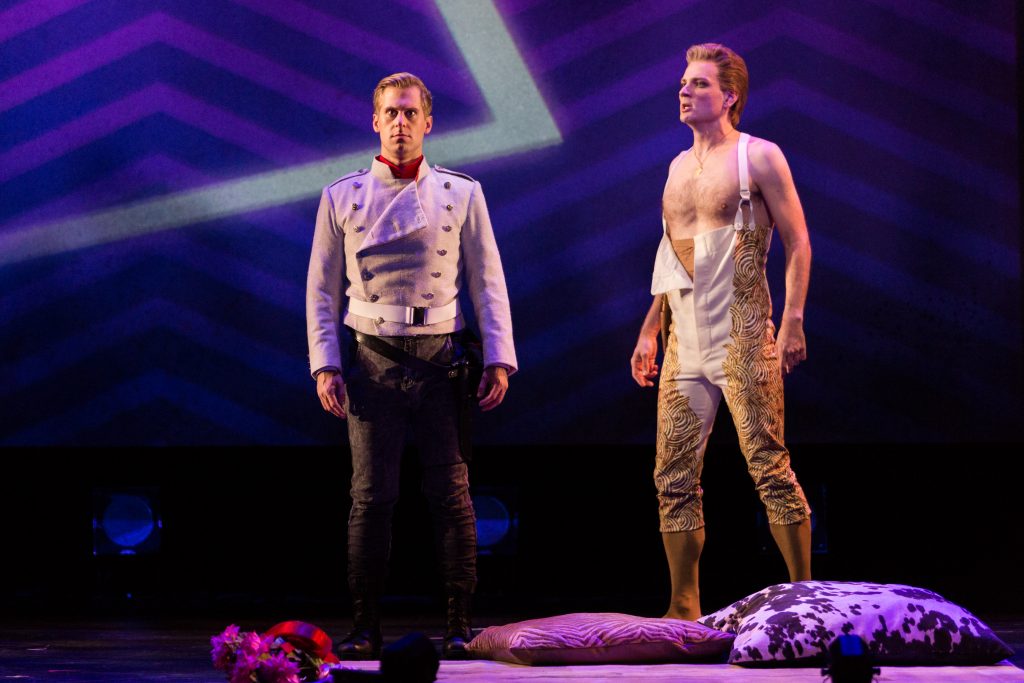

(L-R) Tenor Adrian Kramer (Don Jose) and bass-baritone Ryan Kuster (Escamillo) in San Diego Opera’s The Tragedy of Carmen. March, 2017. Photo by Karli Cadel.

San Diego Opera Presents La tragédie de Carmen by Peter Brook

Music by Georges Bizet

Play by Jean-Claude Carrière, Marius Constant, and Peter Brook

From a novella by Prosper Mérimée

Review by David Gregson

If you have ever wondered what would happen if a so-called Regietheater stage director got ahold of something that was Regietheater already, do not miss San Diego Opera’s treatment of Peter Brook’s La Tragédie de Carmen. Experimental director Alexander Gedeon has taken Brook far out of the equation and made something virtually his own. The result could very well be renamed a travesty or La Parodie de la Tragédie de Carmen. It largely subverts Brook’s essentially serious transformation of Bizet’s opera with a incessant flow of comic schtick. The result is a deliberately induced distancing effect which undermines most of the emotional force of Bizet’s music. It is simultaneously entertaining, iconoclastic and ultimately tepid. This affective flatness is a shame, however, because the cast boasts strong vocal performances from all four of the show’s principals: mezzo-soprano Peabody Southwell as Carmen, tenor Adrian Kramer as Don José, soprano Adriana Churchman as Micaëla, and baritone Ryan Kuster as Escamillo. The show is worth seeing for these wonderful young singers alone.

If you are unclear as to exactly what Regietheater is, it is German for “director’s theater,” a term that describes the work of many contemporary stage directors who purposely ignore the original intent of any given composer so that his or her specific intentions are violated. Stage directions, physical settings, costuming, and chronology are changed at will. Figuring out the point of it all can be painfully obvious or infuriatingly obscure. At its best, Regietheater is exhilarating and enlightening as in most of the work of Peter Sellars. At its worst, it raises supposed political, social and psychosexual subtexts to the surface and treats the audience like idiots.

Of course, mucking about with Georges Bizet’s score for Carmen is nothing new. In 1943 Oscar Hammerstein II adapted the masterpiece as Carmen Jones, an all-black Broadway musical version of the opera, set in North Carolina during WW II. Carmen worked in a parachute manufacturing plant instead of a cigarette factory, and Don José was an American GI named Joe. In 1954 Carmen Jones was made into a major Technicolor film directed by Otto Preminger and starring Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte. Pearl Bailey was sensational in the film as Frankie, a friend of Carmen’s, and was allowed to sing in her own voice, but Dandridge’s singing was dubbed by Marilyn Horne, later a famous Carmen in her own right, and Belafonte’s arias were vocalized by LaVern Hutchinson. I saw the movie when I was in high school and fell in love with it and everybody in it.

Years later in 1983, the innovative stage director Peter Brook came up with his now famous “Carmen in a sandbox,” La Tragédie de Carmen, a far more radical approach to the opera than that of Hammerstein’s. Brook jettisoned all but four singing characters (Carmen, Don José, Escamillo and Micaëla) along with all of the choruses and vocal ensembles and general pageantry. He rearranged and rescored the music for a chamber orchestra of 15 instruments and added some newly composed bits as well. Although he claimed he was getting back to something like the grittiness of Propser Mérimée’s original 1884 novella “Carmen” (the basis for Bizet’s libretto), he changed a number of plot details. A negative critical evaluation of this dickering appeared in The New York Times when Brook’s show was playing at the Vivian Beaumont in 1983.

Brook also produced three stagings of La Tragédie de Carmen with three different casts, one of which can be here found at You Tube. The DVDs, if any, appear virtually impossible to find. The difference between Brook’s work and Gedeon’s will be immediately apparent to anyone who takes the time to view the video. It is clumsily posted in six installments, so you have to dig it out.

Tenor Adrian Karmer (Don Jose) and soprano Andriana Churchman (Micaela) in San Diego Opera’s The Tragedy of Carmen. March, 2017. Photo by Karli Cadel.

For those who go to the opera just to hear a few favorite arias sung live — and, honestly, what real opera lover does that? — the principal singers in San Diego Opera’s production deliver the goods. Southwell has a rewarding rich mezzo and one longs to hear her in a traditional staging of Bizet’s opera. But she is a wonderful and “game” actor who can execute and put up with any sort of directorial shenanigans. The latter might be said for Kramer too, a tenor with a lovely lyric tenor voice and a pleasing stage presence. His “Flower Song,” always a highlight in the opera, was impressive. Churchman was a superb Micaëla, her clear, bright soprano conveying the requisite innocence. Kuster, bare-chested, delivered a macho Escamillo, although I found his fine baritone had a wooly quality that took some getting used to.

Gedeon/Brook’s decidedly anti-romantic, un-Spanish “tragedy” places most of the usually tedious José/Micaëla exchanges first. The dear thing is made to appear ditzy during her entrance with news of her lover’s mother, and later she becomes a zany nympho trying to get José to paw her. No pink pussy hat for this girl! (Some genius director will come up with this idea very soon: a feminist Carmen with all the women wearing pussy hats. Escamillo will look like Trump and tell all his fans to some to his rally in the bullring.) Anyhow, in this show on her first appearance, Carmen, looking like a homeless whore in a tatty overcoat and buxom corset, rises slowly from a heaped-high pile of objets trouvé. At one point, the projections at the back form a series of colored concentric circles that look for all the world like the “That’s all folks” ending of a Warner Brothers cartoon. Only Porky Pig is missing.

Gedeon’s idea (I assume) is to rob the gypsy seductress of all her conventional charms. She becomes a quasi-comical grotesque, and Southwell revels in it. She even, at one early juncture, “comes on” to the audience, crassly egging on applause. José, meanwhile, becomes an easily manipulated puppet, the famously gifted rose is a floppy red cloth saturated with ether. Letting Carmen out of her bonds, he ends up tied by an endless sash that stretches from one side of the stage to the other.

Mezzo-soprano Peabody Southwell (Carmen) and tenor Adrian Kramer (Don Jose) in San Diego Opera’s The Tragedy of Carmen. March, 2017. Photo by Karli Cadel.

One looks in vain in the program for some corroborative evidence that Zuniga (also Garcia) is murdered twice by Don José. Played courageously and with much humor by actor Anthony Nikolchev, Zuniga generates plentiful giggles when various characters try to prop up and animate his corpse in a scene that is more Mel Brooks than Peter Brook. Lending extra campiness to the proceedings is the hilariously androgynous Lillas Pastia (actor Max Cadillac), a pal of Carmen’s who becomes seemingly omnipresent, strutting her stuff solo during the usually exciting bullfight music and participating in one of the show’s several simulated sex scenes. When are Regiedirectors going to really shock us for a change and give us straight-up porno instead of all the oh-so-naughty fake stuff? We even get a fleeting hint at lesbianism in a bedroom scene between Carmen and Micaëla. This scene, however, is one of the best things in the Gideon/Brook piece. A wonderful duet. But I am less enthusiatic about the newly composed music for the death of Escamillo. Yes, he dies this time.

The projections, sets and costumes are a distinctive part of this production. Yuki Izumihara, billed as the scenic and video designer, gives the show a memorable quasi-constructivist look, one of shifting, colorful geometric patterns. The costumes of Adam Alonso are quirky, inventive and sometimes quite handsome. He is also given a credit on the videos. John A. Garofalo, the lighting designer, might like to pay more attention to illuminating faces. The conductor is Christopher Rountree, firmly in control of all the unexpected sounds coming from the San Diego Symphony members in the pit.

Mezzo-soprano Peabody Southwell (Carmen), bass-baritone Ryan Kuster (Escamillo) and actor Max Cadillac (Lillas Pastia, reclining) in San Diego Opera’s The Tragedy of Carmen. March, 2017. Photo by Karli Cadel.

CAST

Peabody Southwell — Carmen

Adrian Kramer — Don José

Andriana Chuchman — Micaela

Ryan Kuster — Escamillo

Alexander Gedeon — Stage Director

Chris Rountree — Conductor

(L-R) Actors Max Cadillac (Lillas Pastia) and Anthony Nikolchev (Zuniga) in San Diego Opera’s The Tragedy of Carmen. March, 2017. Photo by Karli Cadel.

PERFORMANCES

FRI, MAR 10 AT 7PM Buy Tickets

SAT, MAR 11 AT 7PM Buy Tickets

SUN, MAR 12 AT 2PM Buy Tickets

Balboa Theatre

868 Fourth Ave, San Diego, CA 92101