Terrifying Apocalyptic Pessimism: LA Opera’s 2007 “Mahagonny” Revisited

Los Angeles Opera: Kurt Weill/Bertolt Brecht Mahagonny

By David Gregson (Sunday, 25 February 2007)

Los Angeles: February 14, 2007

San Diego, November 1, 2020: This is a reconstruction of a “lost” review.

In their terrifying apocalyptic pessimism, nothing in opera rivals the final few moments of Kurt Weill’s Mahagonny. The stage fills with men and women marching together and carrying placards protesting every conceivable good and evil on earth. Society has become so aimless, amoral and decadent that even God cannot come to its rescue. Nor can He send all the sinners to hell, because, as they themselves complain, “We always were in hell.” Over music of powerful, grim fatality, the chorus sings, “No one, nothing – nothing can help a dead man.” Chords pound out of the orchestra like massive punches to the face. And they keep coming – thunderously, inexorably. The chorus sings words written by Weill’s great collaborator, Bertolt Brecht, whose text is far more powerful in the original German than any in any English translation: “Können einen toten Mann nicht helfen….Können uns und euch und niemand helfen!” You – we — the audience. We’re the ones who cannot be helped.

And we know it’s true. Wagner’s Ring ends with a terrific cataclysmic tone painting representing the end of the world. It’s awesome, to be certain – and there is nothing quite like that in any other opera either. But before this tone painting fades, we hear the famous “redemption through love” leitmotif winding its forgiving way through the orchestra. Though scholars and critics do not agree exactly about the exact name of this melody, there’s little question that it represents a ray of hope. No such ray illuminates the end of Mahagonny.

As a critic, I am afraid I cannot maintain anything resembling pure objectivity in my discussion of Mahagonny. In a sense, I come to this work as a friend of the family. I do not know how old I was when I purchased the three-LP set on Columbia, one I still own and won’t willingly part with. Here it is on my desk: “Columbia Records Presents a Great Masterpiece of the Modern Musical Theatre by Kurt Weill in Collaboration with Bertolt Brecht: Kurt Weill’s ‘Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny’. Starring Lotte Lenya.”

In fact, Lenya (Weill’s widow) produced this album with soloists and the North German Radio Chorus and Orchestra under the direction of Max Thurn and conducted by Willhelm Brückner-Rüggeberg. Infuriatingly, as with so many old LP albums, there is no publication date for the records or for the marvelous accompanying booklet containing original cast photos from the 1930’s, and original production designs by Caspar Neher. With no libretto and no pictures, the shabby, disgraceful reissue of this Columbia recording on a two-CD SONY set shows a copyright of 1956.

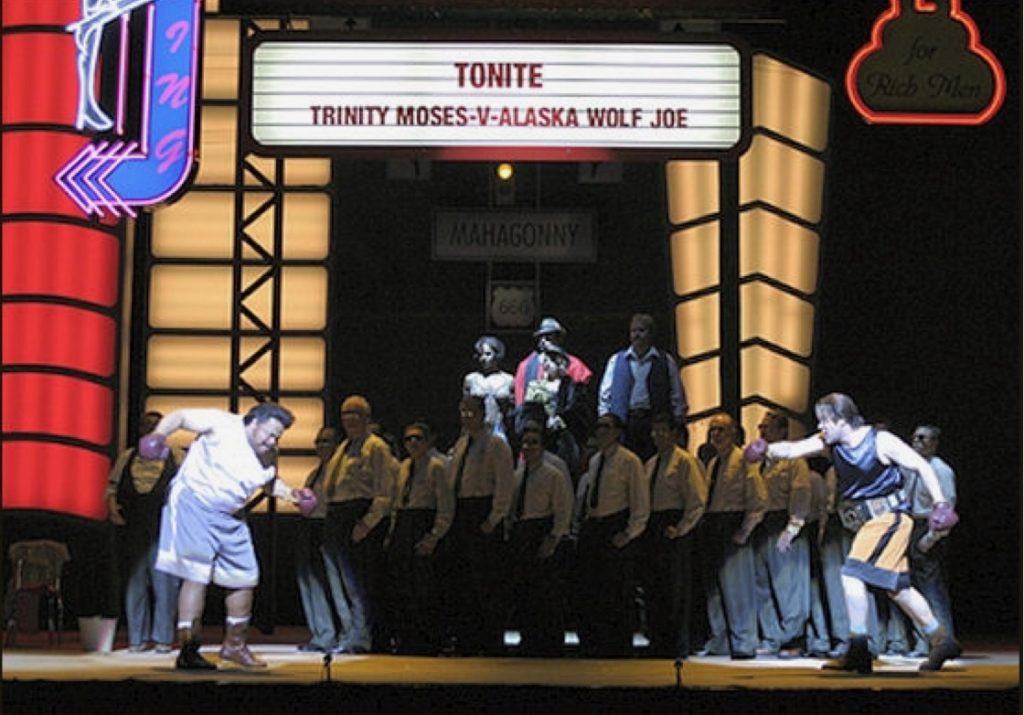

A fatal boxing match in Mahagonny. Photo by Millard

A fatal boxing match in Mahagonny. Photo by Millard

I was among a number of other musical theater fans who purchased this record, loved it to death and gradually memorized every word of it. Friends with directorial aspirations (including a well-known San Diego FM radio announcer) dreamed of producing it, thereby introducing it to a wondering world. None of us were bothered by the work’s moral didacticism. The story: a group of crooks and whores found a here-you-can-do- anything utopia in the middle of an American nowhere and it all goes tragically sour. Sure, it was Marxist to the max – but I found it to be emotionally true. Theoretically Brecht would not have cared for my type of appreciation. His concept of “Epic Theater” was a theater that disengaged one’s emotions and put the brain in gear. The audience was supposed to experience an emotional “alienation effect” that distanced them from emotional identification and made them think about the political/moral issues being raised. It always seemed to me, however, that Brecht’s collaborator, Weill, tended to sabotage this distancing effect, and that Brecht’s poetry was so great that it was impossible NOT to be moved by it. Because the sense of despair was so intense, I would cry at the end of Mahagonny.

Despite the tears, I wasn’t an idiot. I knew what Brecht’s message was. When I was living in San Francisco in the 1960’s, I sang the tunes and lyrics to the accompaniment of real life. I saw the opera’s last act as the second coming of the San Francisco earthquake.

Well – the world has finally discovered this masterpiece and producers ingloriously f—k it up at every opportunity. Why, in LA, does everybody just stand there at the end instead of marching around? Brecht created his own unique kind of theater for this show, and as far as I am concerned, that’s the kind of presentation that works — and directors, to the best of their ability, should be faithful to Brecht’s concept. Stage it Brecht’s way, use Neher’s designs if necessary, make it all look like the Weimer Republic or a movie by G.W. Pabst. Keep Iran, Iraq and the American flag out of it, for God’s sake. We’ll get the idea without being hit over the head. The costumes need not look like every period of American history, Mahagonny doesn’t need to look like Las Vegas, and the prostitutes do not need to look like they’re taking choreography lesson from Bob Fosse.

And, DO IT IN GERMAN. Supertitles have been invented, after all. English translations are insipid as well as inaccurate; the German language gives the show a very special visceral power. And perhaps the most compelling reason for doing the show in German is that bits of it are already written in Pidgin English, a language Brecht imagined might become universal someday. The “Benares Song” (“Where is the telephone?”) and the “Alabama Song” (“Oh show us the way to the next whisky bar”) are hilarious moments of Pidgin English – but when the whole show is in English, they do not make any sense.

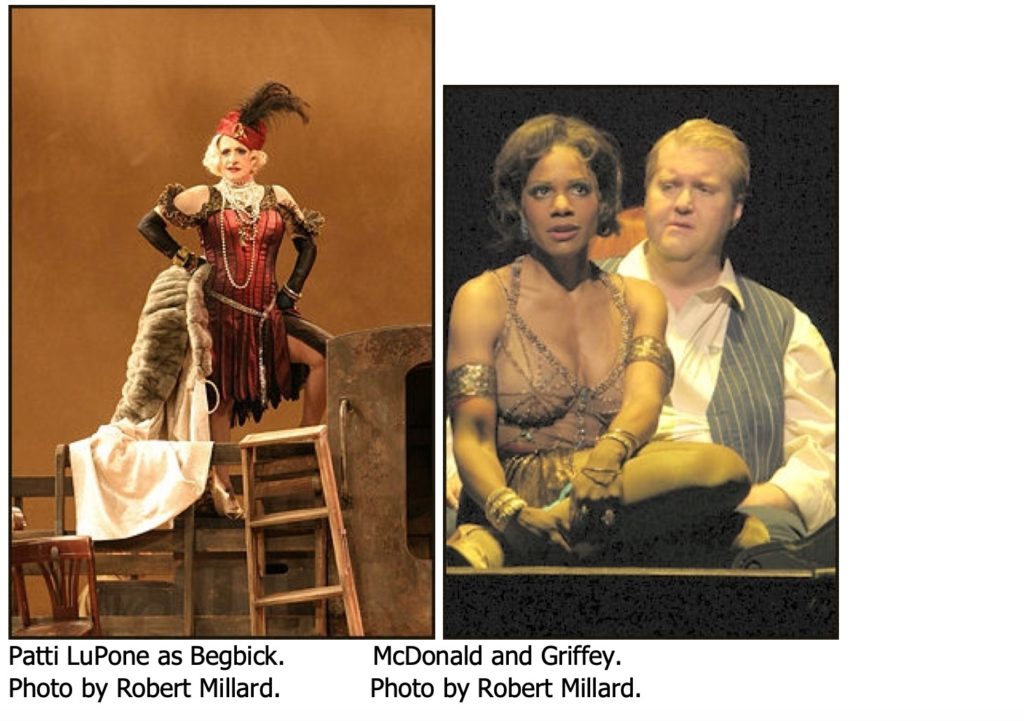

Of course, if you do the show in German, you’re unlikely to get Broadway stars like Audra McDonald and Patti LuPone to come on board. Because I have been so personal in my comments to this point, I’ll go on to say – these two women are my among my

favorite Broadway stars. LuPone has been tremendous in everything I have ever seen her in (including Sunset Boulevard which I saw in London before evil forces took her out of the show), and she gives Brecht’s ruthless Leocadia Begbick her best effort, but she is somehow miscast. And that goes for Audra McDonald, too. She is just too much of a babe, and her voice is so gorgeous it has no cutting edge to it. As Jenny, one really needs a performer more like Lenya – one that suggests German cabaret.

Oh, yes – Mahagonny is supposed to have operatic voices in it. A former close friend of mine, a German who works for the Bayreuth festival, loathes the Lenya recording and prefers another that uses consistently operatic voices throughout. Even Lenya herself sang the part in high soprano at an early point in her career. But Jenny needs something even Audra cannot deliver. The older Lenya seems to convey that mysterious quality.

Now, when it comes to a “distancing effect,” I must confess I “distanced” one part of myself from another while watching this LA production. One might call it a willing suspension of dislike. Dislike of the production, that is. (I had to do that in the recent LAO Tannhäuser as well.) I just tried to enjoy the marvelous Kurt Weill music – which, by the way, is not-so-surprisingly advanced in its harmonic language. Strange sounds, after all, had been emanating from Vienna for sometime already when Weill wrote this. Meanwhile, my seat companion was hating the production’s whole approach which he found sugar coated and misguided. He seemed to find the show splashy and without genuine conviction. I think he was right.

Yet McDonald did look outrageously sexy and sang gorgeously; LuPone was having a ball in campy-trampy outfit; and tenor Anthony Dean Griffey looked the role of the hapless Jimmy McIntrye (who in this production is given a lethal injection for not paying his bar tab), and he vocalized superbly. The rest of the cast was just fine – Robert Wörle as Fatty the Bookkeeper, Donnie Ray Albert as Trinity Moses, John Easterlin as Jack O’Brien, Mel Ulrich as Bank Account Bill, and Steven Humes as Alaska Wolf Joe. The cartoonishly wicked Maidens of Mahagonny, all quite good, are listed below. Conductor James Conlon was booed by the man sitting behind me, but I can only speculate why. He probably thought the orchestra played too well.

In general, the sets designed by Mark Bailey worked quite well. The overall approach was minimalist with bits and pieces suggesting changes of scene, and Bailey preserved Brecht’s wishes to sign-board various human indulgences: DRINKING, EATING, and FIGHTING – and so forth. Thomas C. Hase proved the superior lighting designs.

In the long run, one has to marvel that such a blatantly anti-capitalist show can be put on before a well-off LA audience – and nobody screams in protest. Perhaps mindless conservatives and limousine liberals are the only opera goers?

CAST

Audra McDonald: JENNY SMITH

Patti LuPone: LEOCADIA BEGBICK

Anthony Dean Griffey: JIM MACINTYRE

Robert Wörle: FATTY THE BOOKKEEPER

John Easterlin: JACK O’BRIEN

Mel Ulrich: BANK ACCOUNT BILL

Donnie Ray Albert: TRINITY MOSES

Derek Taylor: TOBY HIGGINS

Steven Humes: ALASKA WOLF JOE

CONDUCTOR – James Conlon

DIRECTOR – John Doyle

SET DESIGNER – Mark Bailey

COSTUME DESIGNER – Ann Hould-Ward

LIGHTING DESIGNER – Thomas C. Hase

SOUND DESIGNER – Dan Moses Schreier

RUNNING TIME:

2 hours 23 minutes