Latest

A Vivaldi Rarity: “Griselda” at Santa Fe Opera

Friday, August 19, Santa Fe Opera

“Griselda” by Antonio Vivaldi

Text by Apostolo Zeno, Carlo Goldoni and edited by Peter Sellars

Adapted from a story in Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”

and derived from several earlier operas on the same theme.

Vivaldi’s “Griselda” is the Surprise Crown Jewel of the 2011 Santa Fe Opera Season

Review by David Gregson

To most students of English literature, the story of “The Patient Griselda” is well known as “The Clerk’s Tale” from Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales.” In it the titular heroine endures without complaint the irrational and monstrous torments of her royal husband. The story provokes a number of strong reactions from the Clerk’s fellow pilgrims, and the Clerk himself comments that the story does not really teach us that married women should tolerate anything resembling Griselda’s fate. He does say, however, one must always submit to the will of God.

Griselda’s awful royal spouse must not be mistaken for God, however — and Chaucer himself interjects that wives should simply not put up with such nonsense at all.

So the moral of the fable is not that any woman should imitate Griselda’s example — and with that in mind, Vivaldi’s 18th-century librettists, helped out in more recent times by stage director Peter Sellars, have turned “Griselda” into a thought-provoking and deeply moving tragic drama. Nobody need fear (although they DO fear it) an anti-feminist lecture. As I have shown, this idea was debunked by Chaucer sometime ago.

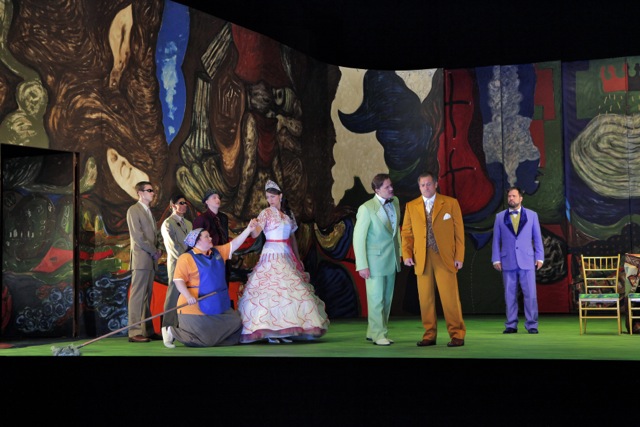

Sellars, one of the most intelligent and musical of the radical stage directors working in opera today, tries very hard to pull us in two directions. One — into the disturbing crazy world of the Gronk mural that dominates the stage throughout the entire evening; and two — into the powerful emotions of the characters delineated by Vivaldi and his librettists.

Gronk is an important Chicano graffiti muralist and performance artist who is enjoying a tremendous vogue at the present time and whose work very much resembles that of the early 20th-century German Expressionist painters. This ties the “Griselda” production strongly into the other finest Santa Fe Opera presentation this season, Berg’s “Wozzeck.” Gronk also has local connections through the University of New Mexico where, in 2003, he worked as part of the Cultural Practice/Virtual Styles project.

Gronk’s painterly vision well complements the tormented irrational state of things in the drama. Even the stage floor, a pool-table green, evokes a sense of dread. This is the green felt table of pointless games and of the powerful generals who plot devastating military maneuvers. Gronk and Sellars and presumably costume designer Dunya Ramicova also give us redundant phallic props to suggest a world of male tyranny. One might even say the automatic weapons we see are always fully erect. One large revolver goes from time to time into the grip of a female in a clear reference to Freud’s notorious theory of penis envy. The person with the penis wields the power, said the infamous Doctor — making waves that have yet to settle down.

I know, for strangers to this tale of psychological torment, some summary is necessary.

Gualtiero, King of Sicily, marries a poor shepherdess, Griselda, but soon begins to have paranoid imaginings that his marriage has damaged his political power and popularity. Griselda bears him a daughter, Costanza, but the twisted Gualtiero pretends to have the baby murdered; he actually gives the child to Prince Corrado to raise in secret.

All gets very goofy and even nastier when many years later the King plans to marry Costanza, his own daughter. She, of course (this is opera), is in already far in love with Corrado’s younger brother, Roberto, and she is not happy about the marriage arrangements. She’d be even unhappier if she were to know the King is her father.

In fairytale fashion, Griselda retreats to the country fleeing the advances of the courtier Ottone, who loves her in vain. Gualtiero saves Griselda from this development by bringing her back to the royal court to serve as Costanza’s slave. Mother and daughter have a sort of “recognition scene” (quite touching in fact), but that does not clear up the confusion. Ottone is still after Griselda and — !!!! — Gualtiero off the wall and out of the blue agrees to a marriage for Ottone just as soon as he (Gualtiero) himself has married Constanza. Griselda says she’d rather die than to go on like this and amazingly Gualtiero takes her back as his his loving spouse. The king also explains the whole absurdly complicated and irrational situation — and then permits Costanza to marry Roberto.

A happy ending — sort of. Sellars leaves us with a bewildered Griselda still mopping the palace floor.

So much praise is due to this superlative cast of singers, it would be impossible to sum up their virtues even if I had the time and bandwidth. The weakest in terms of having a solid grip on Vivaldi’s florid style was the Gualtiero, the well known and well liked tenor Paul Groves. On the other hand, his opening aria is preternaturally difficult and he is easily forgiven for not getting through it unscathed. He also was successful in projecting the image of a rash, macho authority figure — and his well-designed quasi-military costume helped immensely. In fact, I thought all the quirky costumes worked quite well — and the reader may judge from the pictures.

Elsewhere there were nothing but vocal triumphs. Even without very much to sing, contralto Meredith Arwady melted your heart — and Sellars added a Vivaldi “Stabat Mater” just to make her more sympathetic and to give her more to do. Mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard was glorious in every aria, while it was a matter of some musical concern as to who was the greatest countertenor on stage: the always fabulous David Daniels as Roberto or the perhaps even more fabulous Yuriy Mynenko as Corrado. Mynenko revealed a stunning array of vocal colors from one end of the scale to the other. Also perfectly terrific was soprano Amanda Majeski. Her’s was one of the most peculiar trouser roles I have seen in that she seemed to be emanating from a pop-gangsta world I know little or nothing about, but I felt she had lept right out of the Gronk mural.

The stage lighting of James F. Ingalls puzzled me, by the way. At many important junctures the principals were in darkness. What was that all about?

In some ways the biggest hero of this memorably wonderful evening was LA-based conductor Grant Gershon who led the Santa Fe Opera musicians with tremendous energy and attention to detail and emotional impact. This was not your plunge-ahead style of Vivaldi.

In a postscript of sorts, I’d like to point out that Sellars assigns often surprising, grotesque and seemingly incongruous choreographed movements to his performers. This is just his style, and you either accept it or you don’t. They are always an attempt of the director to express some kind of interiority in a new way. I also want to add that the libretto is a solid tissue of metaphorical allusions (thunder, birds, seas, winds, helmsmen etc.) and this gives Sellars the go-ahead to be similarly allusive.

I also want to praise last night’s spectacular thunderstorm provided by Nature and the State of New Mexico. It added immeasurably to an unforgettable experience.

Costanza – Isabel Leonard

Ottone – Amanda Majeski

Griselda – Meredith Arwady

Roberto – David Daniels

Corrado – Yuriy Mynenko

Gualtiero – Paul Groves

Conductor – Grant Gershon

Production/Director – Peter Sellars

Scenic Designer – Gronk

Costume Designer – Dunya Ramicova

Lighting Designer – James F. Ingalls