All That Fuss About Billy: Britten’s ‘Billy Budd’ at Los Angeles Opera

Los Angeles Opera presents Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd

Libretto by E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier, after Herman Melville’s novella

Review by David Gregson, Feb. 24, 2014

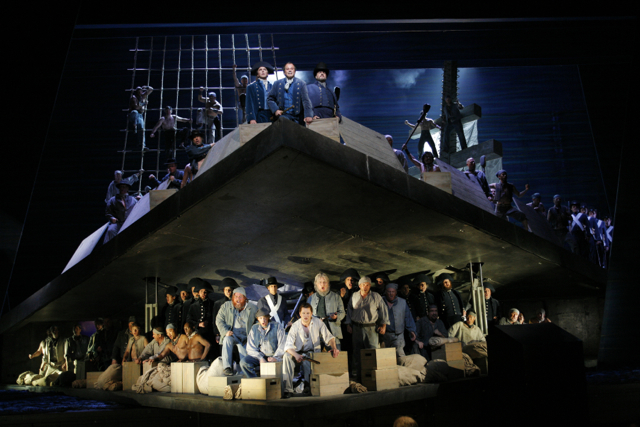

Los Angeles Opera’s current production of Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd, with stage direction by Francesca Zambello and sets and costumes by Alison Chitty, was first seen here in June of the year 2000. By that time it was already five years old, having first been produced at Covent Garden in 1995. So, it’s an old show by now, but it still looks good. In many ways I prefer it to John Dexter’s celebrated production at the Met. Chitty’s concept is, for the most part, agreeably abstract, despite an egregiously in-your-face bit of symbolism — that is to say, the upper portion of an enormous Orthodox Christian cross meant to represent the topgallant mast of a British man-of-war. A large hydraulically operated platform rises and falls when necessary to reveal what’s going on in the lower decks, or to suggest a ship plowing directly forward into the audience. The costumes draw on British naval history and there are literal touches such as rope ladder riggings and glimpses of nautical paraphernalia; otherwise, the decks of the HMS Indomitable are mysterious bits of geometry cast upon the “infinite sea” referenced prominently in the opera.

Those who love or who are still unfamiliar with the work, now have a chance to see it with a top-notch all-male cast, and with an orchestra and chorus under the direction of a superb conductor, James Conlon, who is also an important advocate of the composer. Discounting a certain, perhaps intended passivity on the part of the title character (excellent young American baritone Liam Bonner), the production is a highly satisfying one musically and dramtically, with superb singing from everyone on board.

The source for Britten’s Billy Budd is Herman Melville’s compelling novella of the same name. The genesis of this now acclaimed literary masterpiece is a mind-twirling research project in itself. As I have remarked elsewhere in discussing this work, it has enjoyed a rich life in stage adaptations and is frequently assigned in college literature courses. Students are usually taught that the handsome, naive sailor Billy is essentially a Christ figure; that the evil master-at-arms, John Claggart, is the Devil incarnate; and that Captain Edward Fairfax “Starry” Vere, however well meaning, is Pontius Pilate. The latter equivalency is a terrible over-simplification, because Vere, who veers towards enlightenment and justice (the starry sphere of his nickname), feels the greatest empathy for Billy. For Vere, Billy’s death is the “judgment of God” and it brings the idealistic, truth-seeking captain a lifetime of guilt and soul-searching.

In Melville’s story, Billy, falsely accused of fomenting mutiny and having accidentally killed his accuser, Claggart, with a lightening-bolt blow to the face, meets his ultimate fate by hanging from a yardarm that extends from the central mast of a ship – a mast flanked by two others, like the crosses on Calvary. Melville clearly intended this Christian symbolism. Earlier Billy had been “impressed” — that is taken by force — from a ship called The Rights of Man (also the name of a revolutionary pamphlet by Thomas Paine, a champion of democracy and liberty) and compelled to serve aboard the HMS Indomitable, originally named the HMS Bellipotent by Melville.

I recall reading somewhere that Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose own fiction was deeply infused with allegorical meanings, handed Melville the palm for obscure symbolism after the publication of Melville’s Mardi. So any stage director may be forgiven for giving us unabashed crucifixion images in Billy Budd. Indeed, Zambello gets these pretty much out of the way before the intermission, and Billy’s hanging occurs from a noose dropped down from nowhere, center stage.

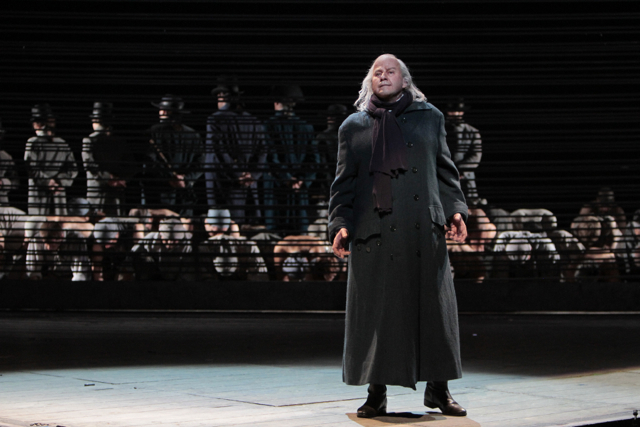

As mentioned above, Liam Bonner, by accident or design, does not generate anything like Billy’s irresistible charisma. His body language is often so understated, his general demeanor so self-effacing, it’s difficult to see what all the fuss concerning this handsome sailor is all about. We mostly have absolutely everybody else’s word for it but cannot see it ourselves. In the wonderful photograph at the top of this page, we can see that Bonner’s Billy is indeed a beauty — and Robert Millard’s picture captures something of Billy’s lamb-like passivity. Ironically, it is in the very scene represented in the photo — the famous “Billy in the Darbies” or “Billy in chains” passage of the opera — that Bonner delivers his most wonderful vocal performance of the night. No one would fault the quality of his singing at any other point in the evening either, but his valedictory aria was superb. Yet, aside from the fact that Bonner seems taller than everyone else, he projects little stage presence. Of course, when Billy stammers — the only flaw in an otherwise perfect person — we cannot help but focus all our attention on him. The work’s creators have made the stammer an earth-shattering event.

Unlike Bonner, bass-baritone, Greer Grimsley, has all the stage presence in the world. As Claggert, he is as aggressively evil as Billy is sweetly understated. Grimsley is ideal in the part. It’s as nasty a role as Verdi’s Iago, and with a really nasty orchestral accompaniment to match Claggart’s declarations of villainy. However, as conceived by Britten, E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier, Claggart is more than a mere devil. He passionately resents the kind of personal perfection that Billy embodies and that he himself totally lacks. He also seems to be the victim of a homoerotic disturbance that makes him turn his sexual attraction for Billy into aggressive, destructive hatred. Director Zambello, however, does not overemphasize this aspect. We see Claggart take Billy’s kerchief, but the homoerotic element remains largely subtextual. This is appropriate, I think, considering the repressed homosexuality of the original novella and of the composer and E.M Forster.

American tenor Richard Croft is simply superb as Vere. The role demands two incarnations: the old man Vere who bookends the story and acts as a framing device; and the younger Vere who participates directly in the action of the story. The sweetness of Croft’s voice beguiled me all evening long. It’s a complicated role to play — and it’s true that Vere frequently comes across as a sort of whiner who complains, “It’s all about me. It’s all about my suffering and guilt!”, and thereby relegates Billy to a secondary role in the drama. One does wonder, why Vere failed to exercise some sort of executive privilege and prevent Billy’s execution. It occurred to me that Zambello — or her deputy here, stage director Julia Pevzner — sees Vere as the central figure and that she, not Bonner, has been responsible for de-emphasizing the title role. In any case, Man’s law — Vere’s law and the law of the military — is at the heart of the dilemma. Billy is the victim.

Although this opera has but three main characters, the cast is actually huge. Popular tenor Greg Fedderly was wonderful as the frantic Red Whiskers; the marvelous British baritone Anthony Michaels-Moore made a memorable Mr. Redburn; bass-baritone Patrick Stillwell was excellent as Lieutenant Radcliff; and Daniel Sumegi was scarily authoritative as Mr. Flint. Bass James Cresswell was most effective as Dansker, the man that warns Billy that “Jemmy Legs” (Claggert) is “down on him,” a text Britten set to an oddly jaunty yet menacing tune. I have listed several other fine performers below. The all-male chorus, including several boys, and the crew of extras was outstanding, for which we give chorus master, Grant Gershon, much thanks.

Musically Britten’s opera is rich with symbolic signature tunes or leitmotivs that he exploits to the max. Conlon is in his element here. As I have written elsewhere on Opera West, those of us that know this work well are moved to tears by themes such as the distinctive “hanging from the yardarm” motif that recurs with devastating emotional power at the climax. Or the incredibly moving 34 chords that sound with dreadful solemnity and at different dynamic levels in different sections of the orchestra. I was pleased to see that these chords are among the things mentioned in the helpful “What To Listen For” article in the LA Opera’s program booklet. There is so much to listen for, really, because Britten will take the slightest bit of material out of a passing remark and then develop its musical contours symphonically over a period of time.

When I first saw this production, I was greatly distressed by the hydraulic floor moving up and down. It is difficult to lose yourself in the magic of a stage production when you fear the performers might be crushed at any moment, but I have had 14 years to get over this. Opera singers today face increasingly dangerous stage environments. Innovative stage directors should be aware that when an audience becomes fearful for the safety of the people on stage, the integrity of the artistic experience is compromised.

CAST

Billy Budd: Liam Bonner

Captain Vere: Richard Croft

John Claggart: Greer Grimsley*

Mr. Redburn: Anthony Michaels-Moore*

Mr. Flint: Daniel Sumegi

Lieutenant Ratcliffe: Patrick Blackwell*

Red Whiskers: Greg Fedderly

Donald: Jonathan Michie

Dansker: James Creswell

Bosun: Craig Colclough

Novice: Keith Jameson

First Mate: Paul LaRosa*

Second Mate: Daniel Armstrong++

Novice’s Friend: Valentin Anikin+

Maintop: Vladimir Dmitruk+

Squeak: Matthew O’Neill

Arthur: Jones Museop Kim++

CREATIVE TEAM

Original Production: Francesca Zambello

Conductor: James Conlon

Director: Julia Pevzner*

Scenery and Costume Designer: Alison Chitty

Lighting Designer: Alan Burrett

Fight Director: Ed Douglas

* LA Opera debut artist

+ Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program member

++ Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program alumnus

Produced in association with the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (London) and the Paris Opera. This production was first seen at Covent Garden on May 30, 1995.

Production made possible by generous funding provided from the

National Endowment for the Arts

and Britten-Pears Foundation.

SCHEDULE

Saturday February 22, 2014 07:30 PM

Sunday March 02, 2014 02:00 PM

Wednesday March 05, 2014 07:30 PM

Saturday March 08, 2014 07:30 PM

Thursday March 13, 2014 07:30 PM

Sunday March 16, 2014 02:00 PM

Please leave comments if you wish.

Well-written account of this superb production, and I agree with your evaluations at every turn. Bonner was the only disappointment, but fortunately not because of his singing, which was quite lovely, but rather his failure to project the charisma of his character. I second your salute to the Met production, which I saw with Thomas Hampson in the title role (1990, I think). I know that memory can embellish a performance, but his Billy Budd was indeed transporting.

One tiny cavil: the ship’s mast is in the shape of a Latin cross. An Orthodox (or Greek) cross has beams of equal length, while a Latin cross is more like the printed letter “t” in proportion.

Thanks, Ken. Posted.