San Diego Opera: “Great Scott” Has Its West Coast Premiere

A quartet, not a trio, but shades of “Der Rosenkavalier” ! (L-R) Mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade as Winnie Flato, soprano Joyce El-Khoury as Tatyana Bakst, mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich as Arden Scott, and countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo as Roane Heckle in San Diego Opera’s GREAT SCOTT, 2016. Photo by Karen Almond.

Great Scott

Jake Heggie, composer

Terrence McNally, librettist

Jack O’Brien, stage director

West Coast Premiere

Review by David Gregson, May 7, 2016

First things first. Opening night appears to have been a great success. Before the house lights finally came on, the carefully chosen cast, along with the composer, librettist and stage director, had taken their bows before a warmly enthusiastic audience. Although the evening was fairly long — 3 hours and 10 minutes including a single intermission — there were only a few defections to be spotted. This, after all, is a dreaded “modern” opera — at least in the sense that is newly minted. Jake Heggie (Dead Man Walking, Moby-Dick and more) is not a progressive or avant-garde composer. He writes in a savvy but heartfelt idiom that he has made his own. Still, local opera goers tend to favor what they are familiar with.

Shortly after the performance, a friend of mine remarked, “I cannot believe that nobody has mentioned that this piece is Jake Heggie’s Ariadne auf Naxos! Heggie is the most Straussian of new composers. His musical lyricism recalls Strauss over and over. Has anyone written about this? The work, his very best so far, is simply gorgeous. And it follows Ariadne in almost every respect. There is a rehearsal of an opera and the performance of an opera, all by the same people. There is a relationship between the composer and the leading singer, although in this case the composer is a ghost. There is a contrast between human and artificial emotions. And I could go on. It’s as great at pastiche as anything by Strauss or Leonard Bernstein.”

Well, that ‘s right — and Ariadne is one of my personal favorites. Nice to have old friends that write reviews for you. But I’ll try to wade in now on my own. Please note the “Comments” option below.

As most people are quick to realize, the title of Heggie’s new work, Great Scott, is an intended comic ambiguity. Followed by an exclamation point, it could be the nearly obsolete expression of astonishment — “Great Scott!” But it chiefly refers to Arden Scott (superb mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich), a brilliant singer at a critical point in the course of her operatic fame. That the title also evokes our thoughts of another entirely fictional character, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby, is another perhaps unintended bit of resonance. Like Fitzgerald’s novel, Heggie’s opera deals with specifically American myths of success and achievement. Unlike The Great Gatsby, however, Great Scott is something of a romp, a romantic comedy spiced with topical satirical jabs and genre parody.

And yet Great Scott is not without a significant human dimension. Both Heggie and his librettist, the noted Broadway playwright Terrence McNally, go to considerable lengths to lend psychological depth to their characters. The fictional American Opera Company’s stage manager, Roane Heckle (wonderful countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo) feels he’s somehow invisible. Perhaps because McNally has given him a Dickensian name, Heckle is searching for full personhood. Meanwhile the same Company’s leading barihunk, Wendell Swann (superbly incarnated by the actual barihunk, Michael Mayes) fears he is just another pretty bod, although he seems awfully anxious to show it off. And so it goes.

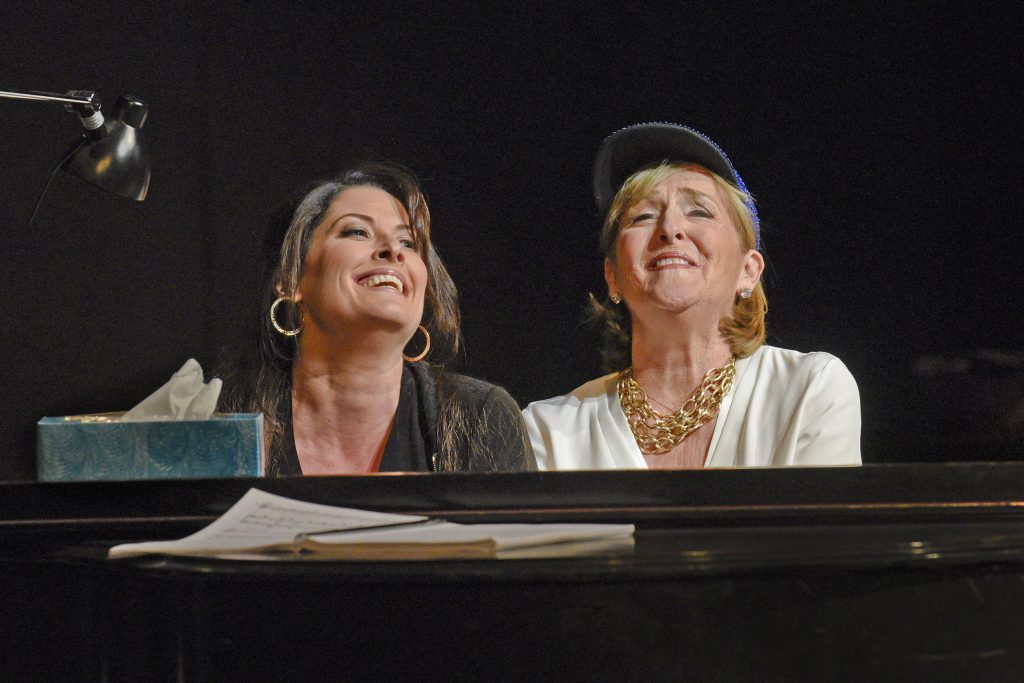

Two wonderful artists, Kate and Flicka. Mezzo-sopranos Kate Aldrich (Arden Scott) and Frederica von Stade (Winnie Flato) in San Diego Opera’s GREAT SCOTT, 2016. Photo by Karen Almond.

As it happens, Great Scott takes us backstage to celebrate the creative process. What it ultimately all adds up to, if anything, has puzzled some commentators, but it’s really not so terribly mysterious.

Great Scott embraces community as well as a world beyond it. The principal characters are all involved in the pursuit of careers, relationships, and the performance of opera itself. Thus Heggie and McNally also give us a skillfully composed and rather witty “opera within an opera,” the faux “newly discovered” bel canto masterpiece, Vittorio Bazzetti’s Rosa Dolorosa, Figlia di Pompei which Arden hopes will boost her artistic reputation and bring new laurels to her hometown opera company.

A fake 19th-century Italian opera about a woman who sacrifices her life by jumping into Mount Vesuvius in order to save the people of Pompeii (in vain, as we know), sounds awfully campy — but Heggie, taking his inspiration directly from Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini, has written some delightful music for his imaginary lost masterpiece. It is funny and affecting in about equal measure. And there is quite a lot of it. In Ariadne auf Naxos, Strauss juxtaposed commedia dell’arte players and serious opera singers — all of them involved with the production of an unforgettably beautiful opera based on Greek mythology. Like my friend, I could go on. How about the Le Bourgeois gentilhomme bits that evoke an older period of music!

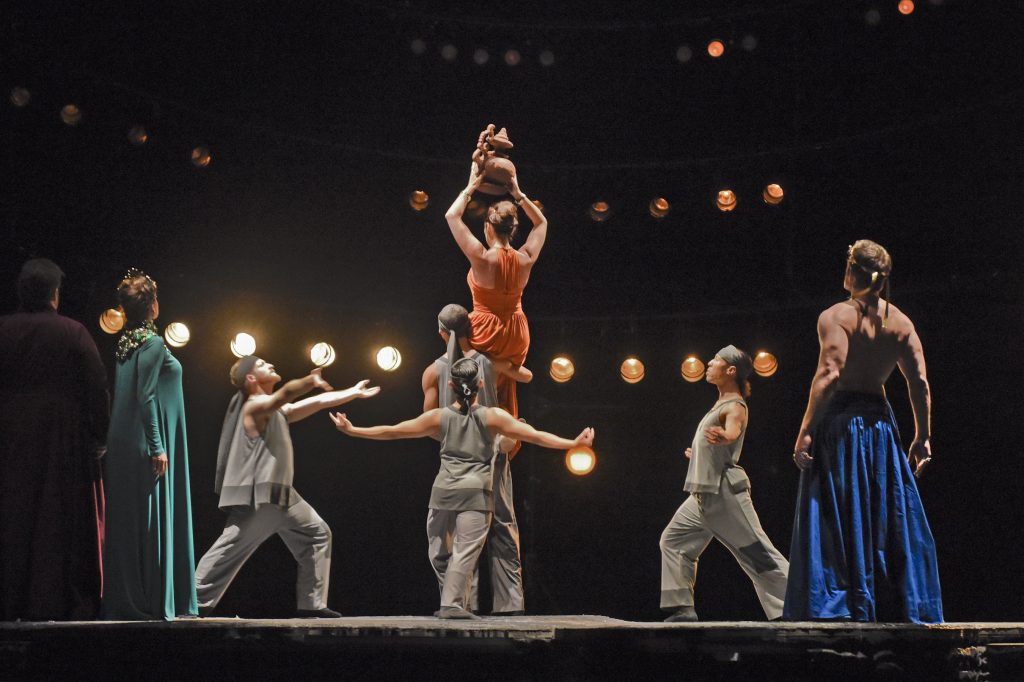

Into the mouth of Vesuvius! A final scene from “Rosa Dolorosa, Figlia di Pompei” the opera within the opera GREAT SCOTT. Photo by Karen Almond, 2016.

A self-referential plot like that of Great Scott is often termed metatheater, that is to say, theater about theater, or in this case an opera about opera. Not so much football about football, however, even though the composer has written a priceless fight song into the overture — and it sounds almost like something by Bellini. The PR pitch for this opera stresses the football connection. Mrs. Edward “Winnie” Flato (the inimitable mezzo Frederica von Stade) is founder and artistic director of the American Opera, but she is also a Grizzlies fan whose husband owns the team. Unfortunately the Super Bowl and Rosa Dolorosa are up against one another on the same Sunday. Arden could sing the National Anthem before the game, but the opportunistic newcomer, Tatyana Bakst (terrific soprano, Joyce El-Khoury) gets the gig herself and makes more than the most out of it.

So Great Scott is also a work of light satire that, among other things, gently pokes fun at America’s obsession with football. Singing the National Anthem at the Super Bowl may confer success and acclaim in a way mere fame on the opera stage cannot. This says something about our cultural priorities. But I do not think the football theme is ultimately the most memorable thing about the opera. The final scenes leave us chiefly with thoughts about Arden and what lies in store for her. Great Scott is chock full of characters and incidents and set pieces (like the priceless alphabet song or nanosecond number in Act One), but I think it is Arden we will remember before anything else. This despite a sumptuous final quartet which brings to mind the glorious trio of soul-baring from Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier.

McNally is no stranger to character development — or to social commentary, amusing and serious, or to metatheatrical plots. The plays, Master Class, The Lisbon Traviata (both involving the diva Maria Callas), Corpus Christi, and the musical The Full Monty spring most readily to mind. I am certain there are several others. McNally is a fine observer of process and is keenly interested in human interaction.

In Great Scott, however, the reignited love affair of Arden and Sid Taylor (baritone Nathan Gunn) seems overly protracted and mundane. Even the music supporting their scenes together shifts into low gear. Heggie has lavished his plushest music, his most romantic strains, if you will, on Arden’s solo scenes. The original Arden (brilliant mezzo, Joyce DiDonato) especially inspired Heggie’s muse. Almost all of Arden’s scenes are gorgeous, or full of vocal display as in the Rosa sequences. I did not hear DiDonato in the original Dallas presentation, but Aldrich seems totally in control of this role and it is difficult to imagine it better sung.

A rekindled love affair. Baritone Nathan Gunn is Sid Taylor and mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich is Arden Scott in San Diego Opera’s GREAT SCOTT, 2016. Photo by Karen Almond.

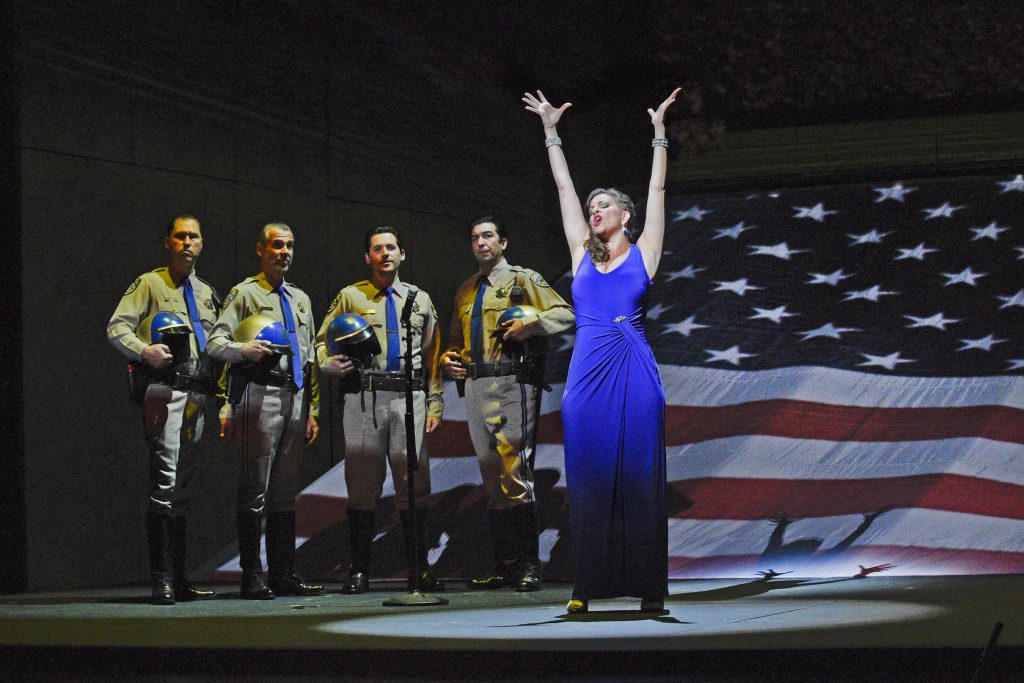

If the opera has a flaw, it is a lack of major dramatic tension. It wants a great arch that pulls us forward to the end. It often seems like a collection of clever scenes, many of them far too cute, all strung together without a really strong thread. What drama exists is not always fresh. There is a sort of “homage” to the classic film, All About Eve, in which a ruthlessly opportunistic super-fan, Eve Harrington (played by Anne Baxter) takes every advantage to undermine the career of her idol, the aging actress Margo Channing (Bette Davis). So in Great Scott we get Tatyana Bakst, a young soprano Arden herself discovered in Eastern Europe, who already possesses the second lead in Rosa Dolorosa, but who will knock Arden out of the spotlight by singing an insanely embroidered (and hilarious) version of the National Anthem at the Super Bowl. As performed by El-Khoury, it is the comic highlight of Great Scott.

Wild Super Bowl “variations” on the Star Spangled Banner. Soprano Joyce El-Khoury is Tatyana Bakst in San Diego Opera’s GREAT SCOTT, 2016. Photo by Karen Almond.

It’s difficult to imagine a better cast than this one. All are superb singers who look and sound totally believable in their parts. The American Opera’s tenor, Anthony Candolino (wonderful Garrett Sorenson) gets several turns playing with Wendell Swan (Mayes), reminding us of male bonding in Puccini’s La bohème, as well as elsewhere. They have fun with vocal stereotypes. Mayes’s character, by the way, reminds one of the younger Nathan Gunn, who frequently showed off his impressive gym results. I was surprised to hear Mayes sounding heftier and fuller voiced that Gunn last night. Frankly, I thought Gunn was underutilized musically. He was a welcome presence, but he had no standout solo moments.

American Opera’s maestro, Eric Gold (excellent bass- baritone Philip Skinner), turns out to have a crush on the stage manager, but it is Skinner’s second role in the show, the ghost of imaginary composer, Vittorio Bazzetti, that is most interesting. Hovering above Arden’s dressing room before the mad scene in Rosa Dolorosa, Bazzetti serves two functions in the story. He is the raisonneur who speaks for Heggie and McNally on the importance of writing new operas, not merely resurrecting old ones as Arden has done. (She had discovered Bazzetti’s opera hidden at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg). Arden has been vacillating about appearing in a new work about Medea, a part that ultimately goes to Bakst instead. Bazzetti also excites a slew of existential questions that carry Arden into her final scene, alone in the opera house. He might even be a version of the Composer in Ariadne.

We are lucky to have such an excellent orchestra in the pit, musicians from the San Diego Symphony under the direction of Joseph Mechavich. Jack O’Brien’s stage direction reveals his deft and expert hand. The set designs are not lavish, but they make impressive use of projections and lighting thanks to Bob Crowley (sets and costumes) and Brian MacDevitt (lighting design). The witty choreography of the campy “Fountain Dance” (in which everything at first goes wrong) is the work of John de los Santos. The chorus is in fine fettle with Charles Prestinari as chorus master.

My earlier piece and some more details about Great Scott — plus more info is here.

Readers are encouraged to leave comments at the bottom of the page — but they are moderated before posting.

Cast

Kate Aldrich: Arden Scott

Nathan Gunn: Sid Taylor

Frederica von Stade: Mrs. Edward “Winnie” Flato

Joyce El-Khoury: Tatyana Bakst

Anthony Roth Costanzo: Roane Heckle

Philip Skinner: Maestro Eric Gold

Garrett Sorensen: Anthony Candolino

Michael Mayes: Wendell Swan

Joseph Mechavich: Conductor

Production

Jack O’Brien: Stage Director

Bob Crowley: Sets and Costumes

Brian MacDevitt: Lighting Design

Elaine J McCarthy: Projection Design

As complete and relevant review as any composer can wish for. Kudos, Janos

Well done, David! A very thoughtful review. I love your insights!

Thanks, Don. Gerry is the “friend”!

You make mention of the projection design but seem to attribute them to Bob Crowley (sets and costumes) or Brian MacDevitt (lighting design). The projections were designed by projection designer Elaine J McCarthy.

Thanks. A great help.

David–delighted that you are back on the opera beat. Your suave voice is unique, and I have missed your sharp perceptions during this recent hiatus. I was going to make comparisons between “Great Scott” and “The Ghosts of Versailles,” but there was so much to comment on already I did not follow that path. But both of these “contemporary” operas start out as spectacle-filled comic operas, but because they don’t know how to conclude their grandiose first acts, they turn into more serious endings that don’t resolve anything.

Thanks, Ken. My review was so long that I just could not work in “The Ghosts of Versailles.” The comparison, however, occurred to me when I first read a plot synopsis months ago. I liked my friend Gerry’s “Ariadne” idea better, but I now see that a reviewer in Dallas came up with that already during the Texas premiere.