Vocal Splendor Trumps All in San Francisco’s ‘The Capulets and the Montagues’

San Francisco Opera

September 29, 2012

Review by JANOS GEREBEN

Forget Shakespeare. Vincenzo Bellini and his hapless librettist, Felice Romani, came up with their own static, nonsensical version of Romeo and Juliet in the 1830 The Capulets and the Montagues – so called by the San Francisco Opera instead of I Capuleti e I Montecchi.

The visual offering of tonight’s premiere of the Bavarian State Opera-San Francisco co-production in the War Memorial was a bewildering combination of Vincent Boussard’s bizarre direction, Vincent Lemaire’s disorienting sets, and Christian Lacroix’s phantasmagorical costumes.

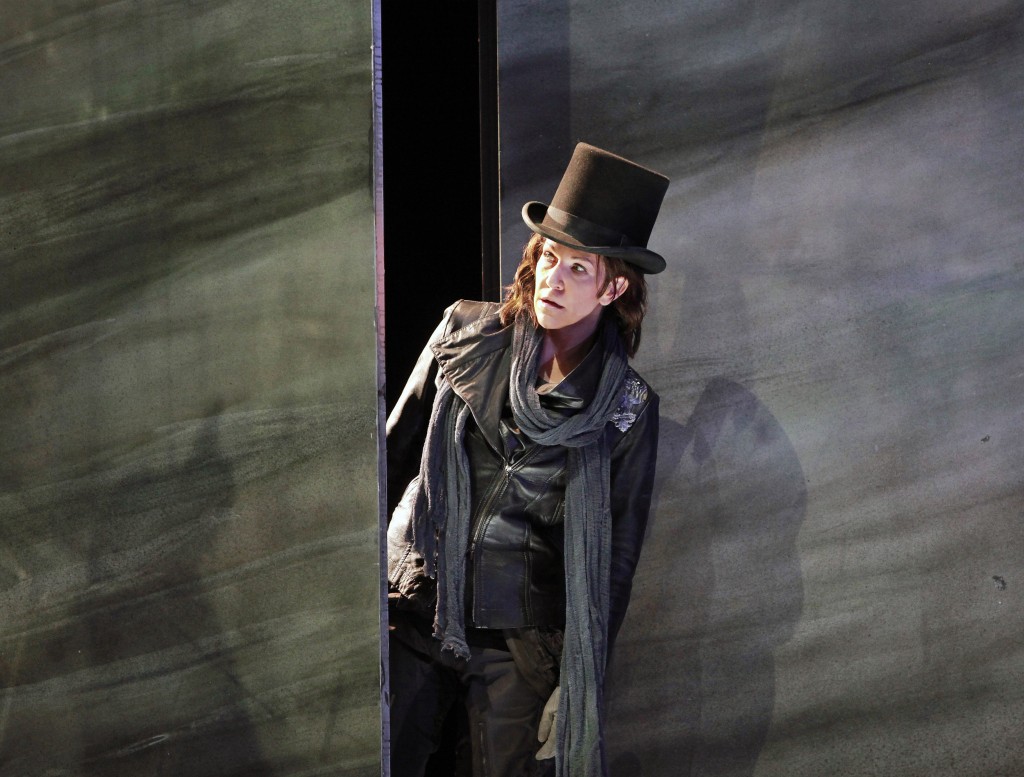

From the opening scene of the Capulets milling about (and blocking the view of soloists) in stovepipe hats, under a cloud of suspended saddles, to the final scene of poor Juliet standing motionless to portray her in death, distractions and self-indulgent “director’s opera” bits piled on one another.

(One interesting variation from Boussard on the old theater convention defined by Chekhov, “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall…”, is “If in the first scene saddles float in the air, they will be carried to battle in the second act.”)

And yet, none of this mattered. Vocally-musically, this is wonderful production. Joyce DiDonato’s Romeo and and Nicole Cabell’s Juliet go right into the record of great performances. They sing radiantly, joyously separately, and — even more — together. DiDonato is well-known and much treasured in these parts, but Cabell is making her debut here, a striking, memorable one.

In addition to the vocal challenges of the Bellini score, Cabell also had to put up with the director’s harebrained instructions to climb up on a narrow shelf to sing one aria, then balance on the edge of a barrier for the next, and then there was that living-statue-while-dead shtick — and through it all, Cabell sang like an angel, the voice soaring through the big hall effortlessly.

Riccardo Frizza conducted the orchestra in an exciting, splendid performance. Ian Robertson’s Opera Chorus had another triumph, top hats and convoluted (but picturesque) costumes notwithstanding.

Eric Owens breezed through the role of Juliet’s father, Adler Fellow Ao Li made a strong impression as Doctor (not Friar) Lorenzo. Saimir Pirgu’s debut here, as Tybalt, didn’t measure up to reviews he has been receiving in Europe. The young Albanian shouted in the first act, and there were miscalculations and small breaks on high notes, but improved by the duet in the crypt with Romeo near the end. There must be some roles better suited for Pirgu than this.

Major and confusing diversions from Shakespeare include Romeo’s previous killing of Juliet’s brother, and cousin Tybalt wanting to marry Juliet (instead of the non-existent Paris), and Juliet’s completely different character from the one in the play. She is more like Donizetti’s Lucia here, conflicted, hesitating, resisting, going mad. From the director: consistent distance between the two alleged lovers.

But to repeat: Listen to DiDonato and Cabell, relish the performance of the orchestra and chorus, and admire Cabell’s Olympic athleticism.

CAST

GIULIETTA: NICOLE CABELL *

ROMEO: JOYCE DIDONATO

TEBALDO: SAIMIR PIRGU *

LORENZO AO LI

CAPELLI: ERIC OWENS

PRODUCTION CREDITS

CONDUCTOR: RICCARDO FRIZZA

DIRECTOR: VINCENT BOUSSARD *

SET DESIGNER: VINCENT LEMAIRE *

COSTUME DESIGNER: CHRISTIAN LACROIX *

LIGHTING DESIGNER: GUIDO LEVI *

CHORUS DIRECTOR: IAN ROBERTSON

* SAN FRANCISCO OPERA DEBUT

Remaining performances:

Wed 10/3/12 7:30pm

Thu 10/11/12 7:30pm

Sun 10/14/12 2:00pm

Tue 10/16/12 8:00pm

Fri 10/19/12 8:00pm

I Capuletti final dress — visual impressions from Orchestra Seat M26:

— The production was both perverse and puzzling, without being very interesting,

— Two scenes opened, each with a lead singer, each facing upstage and singing without moving for quite a long time before turning to the audience. In one of those scenes, we saw the undies-clad backside of the Juliet lead soprano backing toward us, still singing, before turning. In several scenes, one and sometimes both lead singers spent the time sitting, standing, or writhing in the up-left corner of the set. Their actions were generally in slo-mo, and hardly ever interacted. With glazed eyes, they enacted numbed grief and despair–not attitudes to keep an audience’s interest for very long.

— When the tenor started his first number, he was hidden far up-stage behind the townsmen and remained there nearly throughout his entire offering.

–The sets were often darkly lit, so faces were difficult to make out. Did the shiny grey plastic saddles hanging above the stage, first scene, interfere with the downlights?

— The Capuletti townsmen were dressed generally the same–in black and looking vaguely soldier-like. Even the person entering a la peek-a-boo up-center in the first scene looked like everyone else, and it wasn’t until that person sang in a high, metallic voice did we glean that it was the female lead mezzo playing Romeo. Only the bass-baritone, with his stature and cut-away coat/collar/cape item, stood out visually.

— The soprano lead was twice staged in imminently disastrous circumstances, but she survived, gingerly; despite her exquisite singing, the audience could concentrate most mainly on her safely navigating her precarious perches.

— Why did the tenor in the last scene pretend to be walking on a tightrope?

–The two leads sitting together on the floor against the back wall (up-left corner again) and having a little knees-up chat was a teenage-y, home-y touch, but again, they looked and sounded just so unhappy.

— That big gray berm across the stage in the last act–did the stagehands forget it? Oh, I see, the various people hid behind it, appeared, disappeared, and climbed from it up some steep bleachers, effortfully by some of the women.

— The women! Mute throughout, in riotously over-tarted dresses, with frills, billowing folds, and corsages — in their mouths! Did that signify they should shut up, smell good, and do whatever their men wanted?

— End of opera: when the soprano Juliet heard that her mezzo-soprano Romeo was dead, she took poison, a fake poison, meant to–oh, never mind–TMI! When the not-dead Romeo discovered the not-dead Juliet, he, not knowing of her not-deadness, grieved for a while, not believably to us (or to me, anyway), and then took poison to get dead with her. But wait! He then pulled her up, where she stood like a statue, absolutely still for a long time while he raved, and we were entranced, not by him, but by her skill in staying so long still. When he saw she wasn’t really dead, he stood, really dying and singing, while she went berserk, rummaging through her shrouds for any left-over poison, that she should really, really, die with him while he stood there singing and presumably dying.

— We never knew their mutual end exactly, for, as the doomed lovers edged downstage toward the apron, eyes ahead and starkly blank, soldiers behind, we heard, at last, at last, a suggestion of an approaching final double-bar!

Like ·